By Doug Ward

From the trenches, the work to improve college teaching seems interminably slow.

Those of us at research universities devote time to our students at our own peril as colleagues who shrug off teaching and service in favor of research earn praise and promotion. When we point out deep flaws in a lecture-oriented system that promotes passive, shallow learning, we are too often told that such a system is the only way to educate large numbers of students. We seemingly write the same committee reports over and over, arguing that college teaching must move to a student-centered model; that a system established for educating a 19th-century industrial workforce must adapt to the needs of 21st-century students; that higher education’s rewards system must value teaching, learning, and service – not just research.

That’s my perception, at least. During my 15 years as a faculty member, I have seen many positive changes as the benefits of active and engaged learning have seeped into broader conversation and as the need to reform higher education has become part of a growing number of conversations. The largest barriers to change seem immovable, though – especially as we push against them day by day. It’s easy to get discouraged.

So when I heard Mary Huber speak about dramatic changes she had seen in teaching and learning over the last three decades, I wanted to hear more. That was in January 2017 at the annual meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities. I finally had that opportunity a few months later at a meeting of the Bay View Alliance, a consortium of research universities working to improve teaching and leadership in higher education.

I was hoping not only to get a broader perspective on higher education but to gain some reassurance that the work we do to improve undergraduate education matters. I wasn’t disappointed. I never am when I speak to Mary, who has played a crucial role in shaping discussions about teaching and learning over the past 30 years. I have gotten to know her over the past few years through our work in the BVA. She was a founding member of the organization and is now a senior scholar and a member of its leadership team. The insights and leadership she brings to the BVA were honed over many years of work at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, among other organizations.

A key role at Carnegie

At Carnegie, she helped lay the foundation for a movement for better teaching that has blossomed over the last decade. As an anthropologist, she has studied colleges and universities as cultural institutions, offering insights into how they work and why they do what they do. She oversaw Carnegie’s role in the U.S. Professors of the Year Program for many years, directed the Cultures of Teaching and Learning Project and the Integrative Learning Project at Carnegie, and served on the leadership team of the Carnegie Academy for the Scholars. These projects led to books in 2002, 2004, 2005, and 2011.

At Carnegie, Mary Huber was among the “we” that Ernest L. Boyer refers to in the recommendations in an influential 1990 report, Scholarship Reconsidered. That publication took higher education to task for diminishing undergraduate teaching through a rewards structure skewed toward narrowly defined research. She was a co-author of a follow-up book, Scholarship Assessed: Evaluation of the Professorate, and was an early advocate for the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL). She has continued to publish works about SoTL and present conference papers on improving teaching and learning. She also serves as a contributing editor to Change magazine.

Mary covered a lot of territory during a 30-minute conversation on a shady balcony during a mild summer day in Boulder, Colo. She spoke about such things as the rise of pedagogical scholarship within disciplines; the way that education scholarship in the United States developed separately from a line of inquiry followed in the U.K., Canada, and Australia; and the role that teaching centers have played in promoting engaged learning.

“There’s much more conversation today, more places for that conversation, more resources out there that have burgeoned, really, in the past 20 to 25 years,” she said.

She also spoke of faculty members and administrators in terms of the learning they must do about teaching and learning and “remember what it’s like to be a novice in this area” like our students.

She didn’t downplay the challenges, though. In fact, at the end of our interview, she made it clear that those challenges were enormous.

“I don’t think it’s fair to just say that colleges and universities are failing,” she said. “I think society is failing. If they need higher education to do something different, which I think they do, we cannot any longer settle for the kind of education that we have been providing to most of our students. Those good jobs in the workforce and the life they supported are no longer viable for a growing number of college graduates. We need to do better by the students. But we aren’t going to be able to do that without broader social support.”

To understand how we go to that point, though, we have to go back to the 1960s, when Mary Huber completed her undergraduate work at Bucknell University. It’s from that starting point that she explains the changing landscape of teaching and learning through the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

A Q&A with Mary Huber

Mary Huber: My first exposure to teaching in higher education was at a liberal arts college in central Pennsylvania, Bucknell University, a fine liberal arts college. That was in the mid-1960s. So that’s my baseline. From there, I went on to experience with graduate schools, first with my former husband’s and then with my own. After that I began work as a researcher and writer on higher education, first as a research assistant in economics and public policy at Princeton University and then through my roles at the Carnegie Foundation. So it’s kind of been an unbroken chain of some exposure to teaching and learning in higher education at different kinds of institutions.

I think that higher education itself began to change as the proportion of students going on to college changed. That was something that began after World War II, but really took off in the mid to late ’60s. And it brought to colleges and universities a lot of people who weren’t prepared in the traditional sense, at the level that high schools used to prepare college-bound students. There were people going to college who might not have gone in earlier years. That was partly made possible by the growth of community colleges at that time, but many four-year colleges had also opened their doors and brought in new students.

This influx of new students created pockets of pedagogical innovation in the university. I’m thinking in particular about some of the new fields that emerged during that period like composition. Not that composition hadn’t been around, but as a separate field with an identity of its own, it started in the late ’60s and early ’70s, dealing with this issue of students who weren’t prepared for college writing. Composition scholars have persisted in doing excellent work on teaching and learning, with many thoughtful, committed people working to understand and address the problems student writers face in academic writing tasks. There were some other new fields that took off around that time, like ethnic studies and women’s studies, which had a pedagogical twist to their mission. Concerned about how traditional power structures were re-enacted in the classroom, scholars in these fields were trying to create more democratic classrooms that empowered students to move beyond all that. So there were several pockets where there was some very interesting pedagogical thinking going on.

But small groups of people were becoming pedagogically restless in some of the older and larger fields as well. Math was certainly a case in point, spurred by the math wars in the K-12 arena, by the arrival of calculators, and (of course) by high rates of attrition in developmental and advanced introductory mathematics classes.

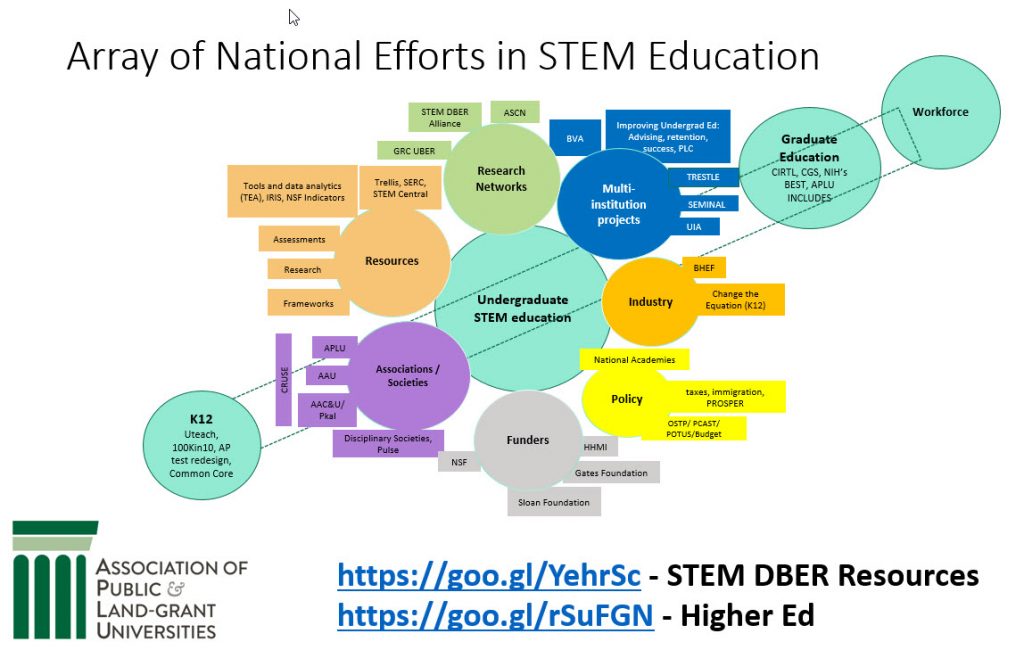

So there were things happening here and there, but it was in pockets. And at some point it spread out. There’s a very interesting article on changes in STEM education policy from roughly the mid-1980s to the late 1990s by Elaine Seymour, who led a center for ethnography and evaluation research right here at the University of Colorado. Her history began with concerns about the pipeline for STEM careers. There weren’t enough people graduating and continuing on in STEM careers, especially not enough women or underrepresented minorities who were coming in and persisting in STEM. That spurred government agencies to support research to explore why that would be. And there was some finger-pointing at pedagogy. But it wasn’t just finger-pointing. It was based on research that was being done at the time on people who did leave STEM to go elsewhere in the university. That, I think, has been another continuing stream of attention to teaching and learning, but not so walled off from other parts of the university. STEM was a large and a growing area in higher education and there was money for research on pedagogical and curricular issues that involved people in mainstream disciplines and institutions making that part of their work. Indeed, by the 2000s, well-known research leaders, like Nobel-prize winning physicist Carl Wieman were lending their prestige and their intelligence and their networks to initiatives to improve STEM teaching in higher education.

Doug Ward: So here we’re talking about the ’90s? 2000s?

MH: Getting into the ’90s and ’00s. But certainly concern about pedagogical and curricular issues in STEM education predated that, going all the way back to Sputnik in the 1960s.

Emergence of a teaching commons

DW: So this surprises me because it sounds like many of the same conversations we are having today: that there’s a concern and certainly a lot of effort over the last 10 years. Why has it been so hard to get some of the changes through to help our students?

MH: Well let me back up just a little to say that I actually think there have been many changes in teaching and learning over the past several decades. Some of them grew out of changes in our fields themselves – especially some of the goals, the way people thought about what they wanted for undergraduates. My field is anthropology and I think anthropology, like many others, has had thinkers who had pedagogical interests, and departments that wanted students to begin to experience what it was like to produce knowledge as professionals do in the field. This was also the case, I think, in history. Yes it’s true that not everybody jumped on board for that. But nonetheless there has been a growing sense that there is just too much knowledge out there now, too much information, too easy to access in this period with the internet and the Word Wide Web. So that was another push that maybe we should be doing something else with undergraduate education than just focusing on mastering content. That’s another thread to add to pipeline and equity concerns. And I think there have been many others – for instance, attention to service and community engagement, not to mention gaining mastery over the new technological tools of the academic trade.

Indeed, if you trace them all out, I think, the picture that emerges is the growth of something that Pat Hutchings and I have called a teaching commons. There’s much more conversation, more places for that conversation today, more resources out there that have burgeoned, really, in the past 20 to 25 years. Disciplinary societies have developed new journals or beefed up old ones about teaching in their fields. There are panels on teaching and learning and curriculum now at meetings that didn’t used to be there. For a long time, it really was a kind of an invisible ground. The traditional forms of teaching – we’ve all experienced them, at Bucknell or wherever we went – but then that’s what shifted.

From private conversations to public discussions

DW: That’s interesting. The way you’re describing it is that there were a lot of private conversations about teaching but really not the public places to have those discussions or the resources to disseminate information.

MH: That’s right. Or to make it part of your life as a teacher. There’s a lovely book by the scholar Wayne Booth. He was a literary critic and scholar of rhetoric at the University of Chicago. He has a wonderful book called The Vocation of a Teacher, published in 1988, which was a collection of his essays and speeches on educational themes. And the resources he cites on how he himself learned to teach are from another era. Not the citations and references you’d expect to find today. There was a footnote listing books that “teach about teaching by force of example” and citing “an obscure little pamphlet” about discussion teaching, but mostly, he said, he learned about teaching through staff meetings and conversations with colleagues. ..There was very little in terms of a formal apparatus of research, or of major thought leaders in teaching and learning. It was very sporadic. I wrote about that back in 1998 or ’99 in an essay on disciplinary styles in the scholarship of teaching. That’s when I was getting into this myself and realizing that there was much more going on than I thought. And I used Wayne Booth’s book an example of the thin web of scholarship on teaching and learning that was common before. Of course, there were thoughtful people who were wise about these things and had given it enough thought to write about it, but they didn’t have much to back it up.

DW: I’m going to veer a little bit because this sort of ties in with an article that you’ve been working on about what is known about teaching for liberal learning. We talked before our interview about how different strands in the scholarship of teaching and learning evolved. Essentially, in the 1970s and 1980s, the British were saying we have a theoretical grounding to our efforts to improve teaching and learning and you Americans don’t. It’s interesting how this kind of practitioner research started to form. How are you seeing the differences?

MH: It is interesting. The way I see it – I’m sure there are others whose standpoint is different – the U.S. never had a very robust area of scholarly research on learning and teaching in higher education. A lot of our focus in our graduate schools of education was on K-12.

DW: Yes.

Different approaches in the U.S. and Europe

MH: For some reason that was not true in the U.K. and Europe. One particularly strong line of work on students’ approaches to and experience of learning was really jump-started by a Swedish research team in the mid 1970’s. That’s when they published their initial papers, presenting work on the experience of learning that was then picked up by colleagues in the U.K., Australia, and Canada. Of course you can trace this theme back a long way. But in the U.S. we didn’t have that strong or coherent an education research group. There have always been a few involved in studies of teaching and learning in higher education, but their work didn’t really shape or constrain what was going on as other groups became interested. This led to a rather diverse set of communities and literatures. The field of learning sciences wasn’t really focused on higher ed, but what they were discovering about memory, prior knowledge and other kinds of things were presented as universally applicable. That was one stream. The professional development people took some of that literature and tried to put it into a frame that would be accessible and helpful to teachers in higher education. And then you had this emergence of the scholarship of teaching and learning, which was a practitioner’s form of research and inquiry into teaching practice. And that was followed by the emergence DBER, which stands for disciplinary-based education research. This involved people in disciplinary fields like chemistry education research and physics education research who had higher education as the domain in which they were examining the ins and outs of STEM learning and teaching.

So you have these many different streams. And over recent years, there have been more and more occasions where people coming from one or the other of those communities can have access to and become aware of what’s going on in the others. For example, longstanding journals like Teaching Sociology or Teaching of Psychology, have been raising the bar on what counts as quality in writing about teaching and learning. It’s no longer enough to tell readers about your clever idea for teaching this topic or that one. We really need to be looking at how students are responding to this kind of pedagogy. So those journals upped the ante for what they would be willing to publish. Other journals in other fields have been more recently founded, and there are now several online journals for the scholarship of teaching and learning itself. More campuses, too, now have centers for teaching and learning that have been sponsoring faculty learning communities and improvement initiatives around issues of teaching and learning that bring people together from across the campus. All these developments have helped widen and deepen the teaching commons, as we have more occasions and more reasons to meet each other and learn about each other’s work.

DW: So I’m visualizing a lot of threads that have been coming together, and the way you’re describing it is that we have shifted from an anecdotal approach to a scholarly approach where there is some substance; there is some foundation. But then where does the criticism from the British fit in?

MH: They had, and continue to have, a relatively small community of researchers who have been building on each other’s work for 30 to 40 years, exploring students’ approaches to learning, among other themes. That’s where these ideas of deep, surface, and strategic approaches to study emerged. They have looked at how that plays out in the lecture format, in the Oxbridge tutorial, in the seminar – indeed, they’ve gone far beyond just that simple trichotomy, and have created a body of knowledge that is often regarded as foundational for new faculty in the U.K. to learn about, or for scholars of teaching and learning there to reference in designing their own inquiries.

In 2008 a group of researchers from the Higher Education Academy at Oxford did a review of the literature on the student learning experience in higher education. You can see that it’s a body of literature that has depth and subtlety and people who are in communication with each other over the years, and that it’s benefited from a long history of exchange between researchers in Australia, Canada, and the U.K. They are a group of people whose careers shift continents and who stay in touch. That is very different from what we have. Very different.

So when the scholarship of teaching and learning caught on in the U.S. among people who are primarily teachers and researchers in their own disciplines – historians, mathematicians, whatever you have – it was both limited and empowered by the relative absence of a thriving local community of researchers in higher education pedagogy. As the scholarship of teaching and learning developed in the part of the world I was working from, at the Carnegie Foundation, we basically urged newcomers: ‘Come on. Draw on whatever you can. You don’t have to master the field of educational psychology or statistics or 40 years of research on this or that educational theme in order to be observant and reflective about what’s happening in your classrooms with your students. If you want to draw on Husserl or Heidegger, be my guest. There are many different ways in which insights from across the academic spectrum can inform your work.’ And I’m very glad. Some of us who were organizing this movement in the U.S. soon learned that your “typical” professor of Chaucer and medieval English literature may not have the time or the interest to tap a whole new (to them) area of study, although they certainly would be interested in addressing questions about their students’ learning. I myself, coming from the humanistic side of anthropology, had trouble with the literature in educational psychology and professional development. I wasn’t interested in it at first. I wasn’t sure about the epistemological grounds on which it was done. I didn’t have the expertise to read it with understanding. But that didn’t mean I wasn’t interested in student learning and couldn’t bring to it some thoughts and methods from my own field. Still, once people like me or that Chaucerian scholar come together around questions of learning with people from a variety of other fields, we soon expand our range of reference, and get better at accessing even the literature in education without being intimidated or offput.

Improving conversations about teaching

DW: I want to ask one more thing. What do you see as the biggest challenges right now in terms of teaching and learning?

MH: Well, I really would go along with the Bay View Alliance on that. I still think that building a stronger, more sophisticated conversation about teaching and learning in departments and disciplines and institutions – building stronger cultures of teaching and learning makes this a better conversation, one people are prepared to engage in more readily – is the challenge that we are facing now.

I’m less worried about professional development in the formal sense. I think that centers for teaching and learning have a big role to play. I think we would make much more progress with this if there were more opportunity in people’s regular, everyday lives as faculty to talk about teaching and learning and to have their contributions recognized. And I think that will happen. I do think there’s been change in the right direction, but there’s a long way to go in many departments before the conversation goes beyond just a one small group of enthusiasts or perhaps the faculty appointed to the curriculum committee. I think the work of those committees focused on undergraduate education need to be upheld as more central to the work of our institutions and not just shoved off to one side.

However, we need to remember, just like we do for our students, what it’s like for a faculty member to be a novice in this pedagogical conversation. But if we keep working on this and have more occasions for graduate students and faculty to talk about teaching and learning, and more department chairs who see this as important and include it in faculty meetings, that will help. Indeed, you could list a whole number of ways in which to make more about our teaching lives public and raise pedagogical literacy to a higher level.

DW: I did a presentation a few weeks ago about the need for elevating teaching in a research university. And the response I got from faculty was, “Yes, but … how do you do that? Because we’re a research university.” This is what we get a lot. “We’re a research university. We don’t have time to carve out for something else.” How do you respond to that?

MH: That is partly why we need leaders who keep reminding us that we’re there for an educational mission – for both undergraduates and graduate students, especially when you are talking about a research university. I think we need our faculty evaluation systems to make a larger space for teaching and educational leadership. But I don’t discount the difficulties given the way the larger political economy of higher education has developed and the competitive world in which institutions believe they live.

DW: And that was the theme at AAC&U, this conflict between prestige and learning, that if we are aiming everything toward prestige, that doesn’t fit with this culture of how do we learn from our mistakes, how do we help all students learn more. That’s a big challenge.

MH: It is a challenge. I was struck yesterday (at the Bay View Alliance Meeting) when Howard Gobstein (of the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities) said that we are going so slow and that society is changing so fast and we aren’t keeping up, that this is urgent. And I’m saying to myself fine, if it’s that urgent why has society pulled away from supporting our public institutions? I think that’s part of the problem. I don’t think we need to take this on ourselves entirely, the critique that we are just not doing enough.

DW: That’s partly what we talked about. We need to be more of an advocate.

MH: We need to be advocating. We need higher education leaders who can make a better case for public support for higher education. We need less talk about and less focus on austerity. I was reading a book recently on public universities – Christopher Newfield’s The Great Mistake. At one University of California institution, in the English major, Newfield said, there was only room for students to have “exactly one” small seminar class because they just don’t have enough faculty to offer more. If the need for our work as educators is as urgent as people think, then we need to more generously resource that effort. Obviously we can be smarter in how we work and improve and do better. And we are going to run into that prestige competition as a countervailing force. That’s how we live. But I don’t think it’s fair to just say that colleges and universities are failing. I think society is failing. If they need higher education to do something different, which I think they do, we cannot any longer settle for the kind of education that we have been providing to most of our students. Those good jobs in the workforce and the life they supported are no longer viable for a growing number of college graduates. We need to do better by the students. But we aren’t going to be able to do that without broader social support. Faculty will need time, security, resources, and encouragement to improve teaching and learning and educational programs so that our colleges and universities can serve today’s students well. That’s my view.

************

This article also appears on the website of the Bay View Alliance.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments