By Doug Ward

Matthew Ohland talks confidently about the best ways to form student teams.

In a gregarious baritone punctuated by frequent, genuine laughs, he freely shares the wisdom he has gained from leading development of a team creation tool called CATME and from studying the dynamics of teams for more than two decades.

Ohland, a professor of engineering education at Purdue, visited KU recently and spoke with faculty members about the challenges of creating student teams and about the benefits of CATME, which has many devotees at KU. The tool, which launched in 2005, is used at more than 1,300 schools worldwide and has led to a long string of research papers for Ohland and others who have worked on the CATME project.

I asked Ohland the question that faculty members often ask me: What are the most important characteristics of a good team? Without hesitation, he offered something that surprised me but that made perfect sense:

“Of all the things you can choose about team formation, schedule is by far the most important,” he said.

That is, if you want students to work together outside class, their schedules must be similar enough that they can find time to meet. If they do all the work in class, the schedule component loses its importance, though.

Before he delves deeper into group characteristics, he offers another nugget of wisdom:

“What you start with in terms of formation is much less important than how you manage the teams once they are formed.”

That is, instructors must monitor a team’s interpersonal dynamics as well as the quality of its work. Is someone feeling excluded or undervalued? Is one person trying to dominate? Are personalities clashing? Are a couple of people doing the bulk of the work? Is a lazy team member irritating others or creating barriers to getting work done?

Whatever the problem, Ohland said, an instructor must act quickly. Sometimes that means pulling a problem team member aside and providing a blunt assessment. Sometimes it means having a conversation with the full team about the best ways to work together.

“Anything – anything – that is going wrong with a team dynamically, the only way to really fix it is face-to-face interaction,” he said.

Delving into team characteristics

In faculty workshops, Ohland delved deeper into the nuances of team formation, asking participants to provide characteristics to consider when creating teams. Among them were these:

- Demographics

- Traditional vs. nontraditional student

- Academic level

- Gender

- Ethnicity

- High performer vs. low performer

- Interest in the class or the subject

- Confidence

- Work styles (work ahead vs. work at last minute)

All of those things can influence team dynamics, he said, and the most consequential are those that lead to a feeling of “otherness.” For instance, putting one woman on a team of men generally makes it difficult for the woman to have her voice heard. Putting a black student on a team in which everyone else is white can have the same effect, as can putting an international student on a team of American students.

“If students have a way of knowing that someone is different, it allows them a way to push them away,” Ohland said. “It’s their otherness that excludes them from certain kinds of team interaction. It’s their otherness that lets people interrupt them.”

Ohland also shared an illustration of an iceberg to represent visible and invisible characteristics of identity. It’s an illustration he uses to help students understand the diverse characteristics of team membership. Gender, race, age, physical attributes and language are among those most noticeable to others. Below the surface are things like thought processes, sexual orientation, life experience, beliefs and perspectives. Awareness of those characteristics helps team members recognize the many facets of diversity and the complexity of individual and team interaction.

Pushback from students

Jennifer Roberts, a professor of geology, uses CATME to form teams in her classes. She said that some students had begun to push back against providing race and gender in the CATME surveys they complete for team formation.

“They went so far as to say that this disenfranchises me because I don’t fit in these categories,” Roberts said.

Ohland said that he understood but that “ignoring race and gender in groups has real consequences.” He suggested explaining the approach to female students this way:

“What I tell my students is that I’m not putting you on a team with another woman so that you will be more successful,” he said. “I am putting on a team with another woman because it changes the way that men behave.”

He cited research that shows that putting more than one woman or more than one person of color on a team improves the performance of everyone by cutting down on feelings of isolation and allowing more views to be heard.

“Men stop interrupting them,” he said. “They start paying attention to their ideas.”

At Purdue, Ohland said, he goes as far as keeping freshmen together on teams in first-year engineering classes, separating them from transfer students who are sophomores or juniors.

“We’ve got to get them by themselves,” Ohland said. “They are at a different phase in life. They’re at a different place academically.”

Preparing students for teams

Ohland said it was important to help prepare students to work effectively in teams. His students go through several steps to do that, including watching a series of videos, engaging in class discussions about how good teams work, reviewing guidelines that team members need to follow, and learning about ways to overcome problems. They also agree to follow a Code of Cooperation, which stresses communication, cooperation, responsibility, efficiency and creativity.

He also explains to students how a student-centered class works, how that approach helps them learn, and what they need to do to make it successful. In a student-centered class, an instructor guides rather than leads the learning process, and students help guide learning, apply concepts rather than just hear about them, reflect on their work and provide feedback to peers.

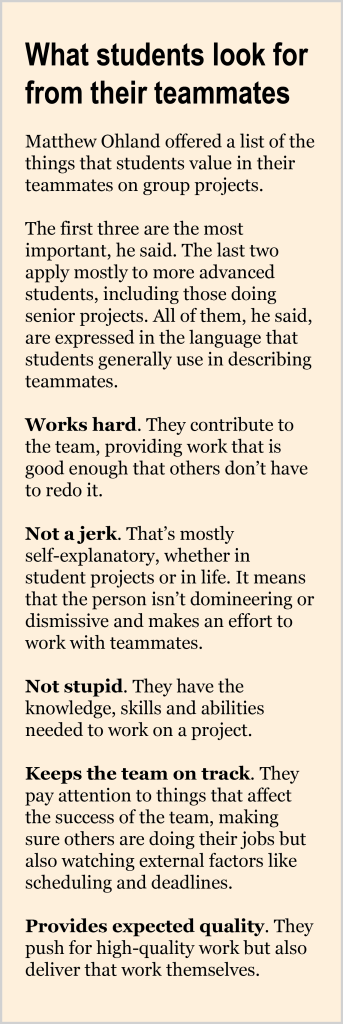

Students must also understand the system they will use to rate peers, Ohland says, and he spends time going over that system in class. It includes measures on how students are contributing to a team, how they are interacting with teammates, how each member works to keep the team on track, how to evaluate the work quality of teammates, and how to evaluate teammates’ knowledge, skills and abilities.

The ins and outs of teams

It would be impossible to detail all of the advice Ohland offered. I would suggest visiting the CATME informational page, where you will find additional information and research about forming and evaluating groups, and keeping them on track. A few other things from Ohland are worth mentioning, though, largely because they come up in many discussions about using teams in classes.

Don’t force differentiation in evaluations. I have been guilty of this, trying to push students to create more nuance in their evaluations of teammates. Ohland said this creates false differentiations that frustrate students and lead to less-useful evaluations.

Learn what ratings mean. For instance, if team members give one another perfect scores, it could mean they are working well together and want the instructor to leave them alone. It could mean that students didn’t take the time to fill out the evaluations properly or it could mean that students felt uncomfortable ranking their peers. In that last scenario, Ohland sits down with a team and explains why it is important to provide meaningful feedback. If they don’t, individuals and the team as a whole lack opportunities to improve.

“That seems to help get them think about the value of the exercise,” Ohland said. “It gets that discussion going about why are we doing this and why it’s important not to just say everybody’s perfect.”

Keep the same teams (usually). Changing teams during a semester can create problems, he said, because high-functioning teams don’t want to disband and teams that are making progress need more time to work through kinks. Only the dysfunctional teams want to change, he said. The best approach is to find those dysfunctional teams and help them get on track.

The one exception to that guideline, he said, is when learning to form teams effectively is part of a class’s goals. In that case, an instructor should form teams more than once so that students get practice.

Evaluate teams frequently. Ohland recommends having peer evaluations every two weeks. Research shows that evaluations should coincide with a “major deliverable,” he said. That makes students accountable and increases the stakes of evaluations so that students take them seriously.

Create the right team size. In some cases, that may mean three or four. In others, six, eight, 10 or even more.

“Team size depends on what you are asking students to do,” Ohland said. “The critical thing about team size is that you need enough people on a team to get the work done that you are asking them to do – the quantity of work. You also need enough people on a team to have all the skills necessary to do the work represented.”

It also depends on the layout of a room. For instance, a team of three in a lecture hall is ideal because students can have easy conversations. A group of four in the same setting will leave one member of the team excluded from conversations.

A final thought

Research by Ohland and others has helped us better understand many aspects of effective student teams. I asked Ohland whether those components mesh with what students look for in teammates.

Making that connection, he said, “is the holy grail of teamwork research.”

“It’s so difficult to get an absolute measure of performance,” he said. “If our goal is learning, that’s a different goal than a competitive, objectively measured outcome in a project.”

Some data point to a connection between learning and team performance, but proving that is a work in progress.

“We’re getting there,” Ohland said.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments