By Doug Ward

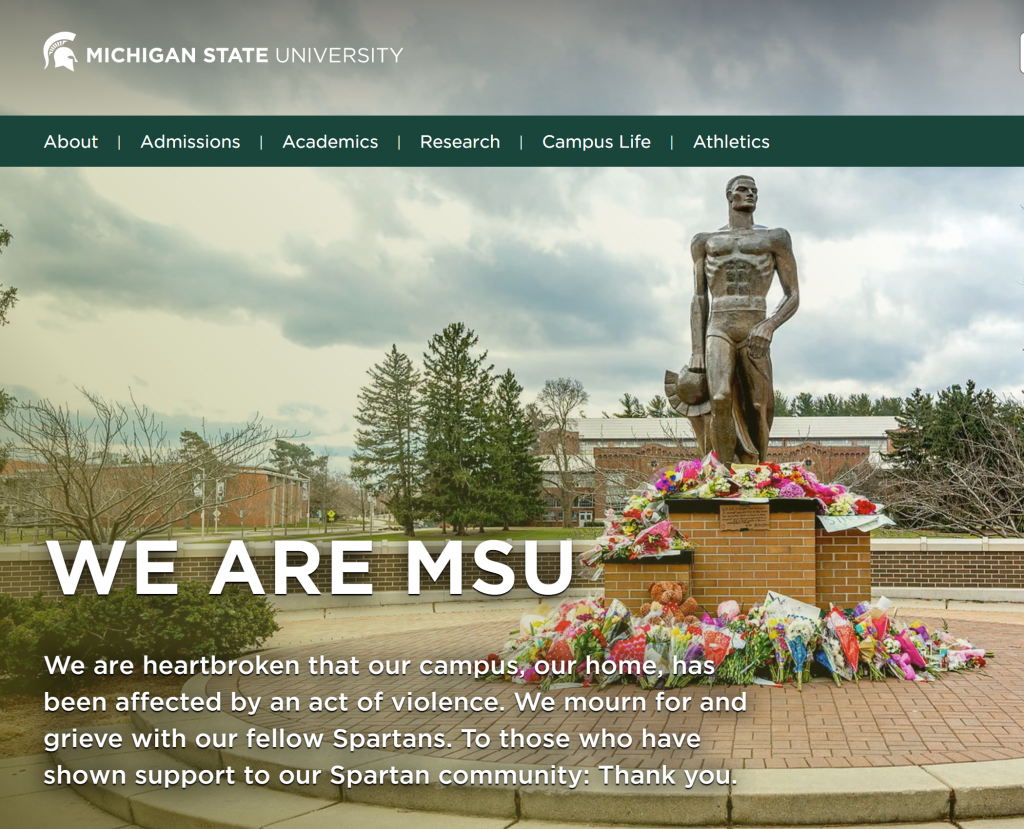

Instructors have raised widespread concern about the impact of generative artificial intelligence on undergraduate education.

As we focus on undergraduate classes, though, we must not lose sight of the profound effect that generative AI is likely to have on graduate education. The question there, though, isn’t how or whether to integrate AI into coursework. Rather, it’s how quickly we can integrate AI into methods courses and help students learn to use AI in finding literature; identifying significant areas of potential research; merging, cleaning, analyzing, visualizing, and interpreting data; making connections among ideas; and teasing out significant findings. That will be especially critical in STEM fields and in any discipline that uses quantitative methods.

The need to integrate generative AI into graduate studies has been growing since the release of ChatGPT last fall. Since then, companies, organizations, and individuals have released a flurry of new tools that draw on ChatGPT or other large language models. (See a brief curated list below.) If there was any lingering doubt that generative AI would play an outsized role in graduate education, though, it evaporated with the release of a ChatGPT plugin called Code Interpreter. Code Interpreter is still in beta testing and requires a paid version of ChatGPT to use. Early users say it saves weeks or months of analyzing complex data, though.

OpenAI is admirably reserved in describing Code Interpreter, saying it is best used in solving quantitative and qualitative mathematical problems, doing data analysis and visualization, and converting file formats. Others didn’t hold back in their assessments, though.

Ethan Mollick, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, says Code Interpreter turns ChatGPT into “an impressive data scientist.” It enables new abilities to write and execute Python code, upload large files, do complex math, and create charts and graphs. It also reduces the number of errors and fabrications from ChatGPT. He says Code Interpreter “is relentless, usually correcting its own errors when it spots them.” It also “ ‘reasons’ about data in ways that seem very human.”

Andy Stapleton, creator of a YouTube channel that offers advice to graduate students, says Code Interpreter does “all the heavy lifting” of data analysis and asks questions about data like a collaborator. He calls it “an absolute game changer for research Ph.D.s.”

Code Interpreter is just the latest example of how rapid changes in generative AI could force profound changes in the way we approach just about every aspect of higher education. Graduate education is high on that list. It won’t be long before graduate students who lack skills in using generative AI will simply not be able to keep up with those who do.

Other helpful research tools

The number of AI-related tools has been growing at a mind-boggling rate, with one curator listing more than 6,000 tools on everything from astrology to cocktail recipes to content repurposing to (you’ve been waiting for this) a bot for Only Fans messaging. That list is very likely to keep growing as entrepreneurs rush to monetize generative AI. Some tools have already been scrapped or absorbed into competing sites, though, and we can expect more consolidation as stronger (or better publicized) tools separate themselves from the pack.

The easiest way to get started with generative AI is to try one of the most popular tools: ChatGPT, Bing Chat, Bard, or Claude. Many other tools are more focused, though, and are worth exploring. Some of the tools below were made specifically for researchers or graduate students. Others are more broadly focused but have similar capabilities. Most of these have a free option or at least a free trial.

- Research assistants like Research Rabbit, ARIA (an add-on to Zotero), Litmaps, Connected Papers, and ClioVis help scholars find and organize literature, visualize connections among ideas, share collections of research, and keep up with new research.

- Search tools like Consensus, Elicit, Scite, SciSpace, Snowball, System Pro, You, Metaphor, and Inciteful help guide researchers toward specific types of literature.

- Tools for interacting with articles. These allow researchers to query literature with natural language questions and to find ideas or connections they might have overlooked. They include Explainpaper, which allows you to highlight text and ask for explanations; PaperBrain; Sharly, which has a generous free version; ChatPDF; MapDeduce; Census GPT, which connects to U.S. Census data; Humata; Upword; OpenRead; PDF.ai; Kadoa; and Cerelyze, which allows you interact with articles and translate method into code.

- Summary tools provide quick synopses of articles, papers, and books, making it easier to work through large amounts of literature. These include Scholarcy, which highlights key areas of academic articles and allows you to build a personal library; Lateral; MapDeduce; ShortForm.ai, which uses a browser plugin; TinyWow, which offers a suite of free AI-powered tools; Summarize.tech and Eightify, which summarize YouTube videos; and BooksAI, which provides summaries of books.

- Several data tools allow researchers to query their quantitative data with natural language questions. These include Julius; Formulas HQ; Chatwithdata; Chatcsv; ChatNode; Tomat; Chartify; DataSquirrel; Chaindesk; and JADBio, which focuses on genomics, medicine, health, and drug discovery. Web-scraping tools like Simplescraper help automate time-consuming data-gathering.

- Writing tools like Jenni, Paperpal, Writefull, and Wisio promise to make academic writing easier.

How to use Code Interpreter

You will need a paid ChatGPT account. Jon Martindale of Digital Trends explains how to get started. An OpenAI forum offers suggestions on using the new tool. Members of the ChatGPT community forum also offer many ideas on how to use ChatGPT, as do members of the OpenAI Discord forum. (If you’ve never used Discord, here’s a guide for getting started.)

Recent Comments