By Doug Ward

A recent meeting at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine achieved little consensus on how best to evaluate teaching, but it certainly showed a widespread desire for a fairer system that better reflects the many components of excellent teaching.

The National Academies co-sponsored the meeting earlier this month in Washington with the Association of American Universities and TEval, a project associated with the Center for Teaching Excellence at KU. The meeting brought together leaders from universities around the country to discuss ways to provide a richer evaluation of faculty teaching and, ultimately, expand the use of practices that have been shown to improve student learning.

My colleague Andrea Greenhoot, professor of psychology and director of CTE, represented KU at the meeting. Members of the TEval team from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, the University of Colorado, Boulder, and Michigan State University also attended. The TEval project involves more than 60 faculty members at KU, CU and UMass. It received a five-year, $2.8 million grant from the National Science Foundation last year to explore ways to create a fairer, more nuanced approach to evaluating teaching.

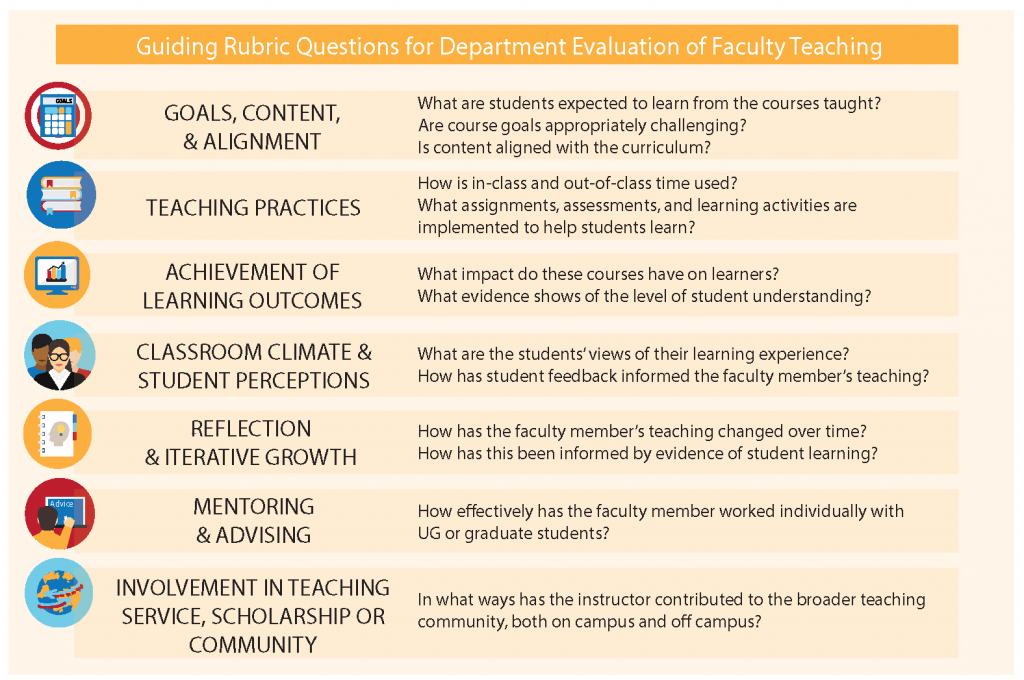

The TEval project, which is known as Benchmarks at KU, has helped put KU at the forefront of the discussion about evaluating teaching and adopting more effective pedagogical strategies. Nine departments have been working to adapt a rubric developed at CTE, identify appropriate forms of evidence, and rethink the way they evaluate teaching. Similar conversations are taking place among faculty at CU and UMass. One goal of the project is to provide a framework that other universities can follow.

Universities have long relied on student surveys as the primary – and often sole – means of evaluating teaching. Those surveys can gather important feedback from students, but they provide only one perspective on a complex process that students know little about. The results of the surveys have also come under increasing scrutiny for biases against some instructors and types of classes.

Challenges and questions

The process of creating a better system still faces many challenges, as speakers at the meeting in Washington made clear. Emily Miller, associate vice president for policy at the AAU, said that many universities were having a difficult time integrating a new approach to evaluating teaching into a rewards system that favors research and that often counts teaching-associated work as service.

“We need to think about how we recognize the value of teaching,” Miller said.

She also summarized questions that had arisen during discussions at the meeting:

- What is good teaching?

- What elements of teaching do we want to evaluate?

- Do we want a process that helps instructors improve or one that simply evaluates them annually?

- What are the useful and appropriate measures?

- What does it mean to talk about parallels between teaching and research?

- How can we situate the conversation about the evaluation of teaching in the larger context of institutional change and university missions?

Noah Finkelstein, a University of Colorado physics professor who is a principal investigator on the TEval grant, brought up additional questions:

- How do we frame teaching excellence within the context of diversity, equity and inclusion?

- How can we create stronger communities around teaching?

- How do we balance institutional and individual needs?

- How do we reward institutions who improve teaching?

- When will AAU membership be contingent on teaching excellence?

Moving the process forward

Instructors at KU, CU and UMass are already grappling with many of the questions that Miller and Finkelstein raised.

At KU, a group will meet on Friday to talk about the work they have done in such areas as identifying the elements of good teaching; gathering evidence in support of high-quality teaching practices; developing new approaches to peer evaluation for faculty and graduate teaching assistants; providing guidance on instructor reflection and assessment; and making the evaluation process more inclusive. There have also been discussions among administrators and Faculty Senate on ways to integrate a new approach into the KU rewards structure. Considerable work remains, but a shift has been set in motion.

KU faculty and staff share insights on teaching

Several KU faculty members have recently published articles about their inquiry into teaching. Their articles are well worth the time to read. Among them:

- Patterns in curricula. Josh Potter, the documenting learning specialist at CTE, writes in Change magazine about a model he has created for showing how students move through classes in a curriculum.

- Physics. Sarah LeGresley Rush, Jennifer Delgado, Chris Bruner, Michael Murray, and Chris Fischer write about their work in rethinking introductory physics. Their paper, published in Physical Review Physics Education Research, was also featured in the online magazine of the American Physical Society.

- Journalism. Carol Holstead, associate professor of journalism and mass communications, writes about the importance of learning students’ names. Her article appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Music therapy. Abbey Dvorak, associate professor of music therapy, writes in the Journal of Music Therapy about using a research assignment that involves an entire class pursuing a single question. She also explains the approach in a video.

- History. Tony Rosenthal, professor of history, writes in The Journal of Urban History about an interdisciplinary journey he took in creating assignments and materials for an undergraduate history course called Sin Cities.

Briefly …

- Writing in EdSurge, Bryan Alexander says that “video is now covering a lot of ground, from faculty-generated instructional content to student-generated works, videoconferencing and the possibility of automated videobots.” The headline goes beyond anything in the article, but it nonetheless raises an interesting thought: “Video assignments are the new term paper.”

- The Society for Human Resource Management writes about a trend it calls “microinternships,” which mirror the work of freelancers. Microinternships involve projects of 5 to 20 hours that the educational technology company Parker Dewey posts on a website. Students bid on the work, and Parker Dewey takes a percentage of the compensation. The company says it is working with 150 colleges and universities on the microinternship project.

- Writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, Aaron Hanlan argues that by relying on a growing number of contingent, “disposable” instructors, “institutions of higher education today operate as if they have no future.” In following this approach, tenured faculty and administrators “are guaranteeing the obsolescence of their own institutions and the eventual erasure of their own careers and legacies,” he argues.

- EAB writes about the importance of reaching out to students personally, saying that email with a personal, supportive tone can be like a lifeline to struggling students.

- Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments