By Doug Ward

We often idealize a college campus as a place of ideas and personal growth, but we have to remember that danger can erupt without notice.

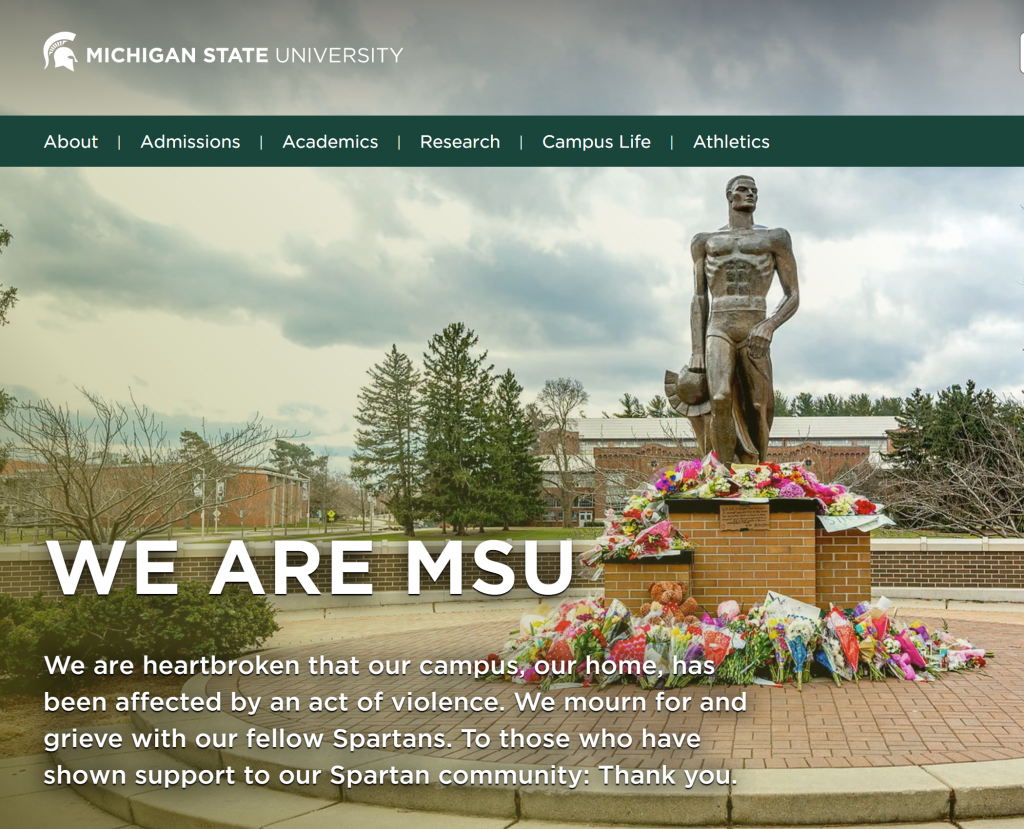

The shootings at Michigan State this week were, sickeningly, just the latest in string of killings over the past year that also involved students or faculty members from Virginia, Iowa State, and Arizona, according to Inside Higher Ed. At Idaho, a Ph.D. student has been charged with killing four undergraduates. At K-12 schools, 332 students were shot on school property last year and 35 this year so far, according to the K-12 Shooting Database. Twenty-one of those students died.

A colleague at Michigan State talked about the surreal feeling of dealing with a mass shooting on a home campus. The frequency of such shootings has made gruesome acts seem distant and almost mundane. The headlines flicker past, and the killings always seem to take place someplace else — until they don’t.

There is no clear way to predict those types of mass killings, although researchers says that assailants are usually male and have a connection to a campus. There are steps we can take to protect ourselves, though.

In a visit to a pedagogy class I taught in 2017, two members of the KU Police Department, Sgt. Robert Blevins and Sgt. Zeke Cunningham, offered excellent advice on how to prepare and what to do if you find yourself in peril.

What you can do now

Know your surroundings

Familiarity with the campus and its buildings could prove crucial in an emergency. Know where exits are, Cunningham said. Learn where hallways and stairways lead. Walk around buildings where you work or have class and get a sense of the building layout and its surroundings. Make sure you know how to get out of a classroom, lab, or other work space. Large rooms usually have several doors, so pay attention to where they are and where they go. That will help you make decisions if you find yourself in a crisis.

Sign up for campus alerts

The university sends announcements during emergencies, so make sure you are signed up to receive alerts in ways you are most likely to see them.

Pay attention

We are often lulled by routine and easily distracted by technology. In a classroom – especially a large classroom – it can be easy to shrug off a disruption in another part of the room. If something makes you uneasy, though, pay attention and take action, whether you are in a classroom, a hallway, or a building, or outside traveling across campus.

“Trust that voice in your head, because you’re probably right,” Blevins said.

Call the police

If you see a problem and think it could be an emergency, call 911. Don’t assume someone else already has. Blevins said the police would rather respond 100 times to something that ends up being innocuous than to show up to a tragedy that could have been prevented if someone had called. Different people also see different things, Cunningham added, and collectively they can provide crucial details that may allow the police to create a clearer picture of what happened.

What to do during an emergency

If you find yourself in an emergency, the officers said, follow these steps:

Stay calm

That can help you remember where to find exits and how to help others find safety. That is especially important for instructors.

“If you panic, the students are going to panic,” Cunningham said. If students make a mad rush for the door, he said, someone will get hurt. “So try to remain calm. I know that’s easier said than done in situations like this, but that will help the students stay calm.”

Run. Hide. Fight.

That is the approach that many law enforcement agencies recommend if there is an active shooter in your area. Michigan State sent those very instructions to students and faculty Monday night.

Run. If you can leave a dangerous area safely, go. Don’t hesitate. That’s where knowledge of the exits and the area around a building can make a difference. Encourage others to leave and get as many people to go with you as possible. Break windows to create an exit if you need to, as students at Michigan State did this week. If others are trying to go toward a dangerous area, warn them away.

Hide. If you are inside a room and cannot escape safely, turn off the lights and lock and barricade the doors with whatever you can find. Stay low and out of sight. Flip over tables and crouch behind them. Hide behind cabinets or anything else in a room. Silence your phone and stay quiet. Close any blinds or curtains. Many smaller rooms have locks you can engage, so lock the doors if you can. You usually can’t lock doors in large lecture halls, so barricade the doors with anything you can find. In some cases, the officers said, people have lain on the floor with their feet pushing against the door.

Those who commit mass shootings usually know they have only limited time before the police arrive, Blevins said, so they act quickly. If a door is locked, the shooter will usually pass by and look for one that isn’t locked. If lights are off, the person is more likely to pass by and seek out a room that looks like someone is inside. If you are in a room with many windows, get out if possible because the attacker will probably see you. If you can’t get out, conceal yourself as best you can.

Fight. As a last resort, fight back against an attacker. Use whatever you have available as a weapon: chairs, drawers, bottles, cords. Work together to bring down the attacker. If a gunman barges into a room and you don’t have a means of escape, you have no choice but to fight, Cunningham said.

“It sounds weird, but if they are an active shooter, you cannot hold back,” he said. “Pick up a chair and smash him in the face. Kick him. Punch him. Pick up the fan and throw it and do whatever you can to get them to stop.”

The video below includes a dramatization of those practices in action. It’s a sad reality that mass shootings take place on campuses, but it makes sense for us to be aware of our surroundings wherever we are. The shootings at Michigan State emphasize that.

Other resources

- KU Police website

- Safety at KU, Provost’s Office.

- FBI website

- Michigan State murders: What we know about campus shootings and the gunmen who carry them out, by David Riedman and James Densley, The Conversation (14 February 2023).

Doug Ward is associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Recent Comments