By Doug Ward

I’m frequently awed by the creative, even life-changing, work that students engage in.

The annual Service Showcase sponsored by the Center for Service Learning, provides an impressive display of that work. This year’s Showcase took place last week. As a judge for the Showcase over the past two years, I’ve learned how deeply some students have become involved in the community. Here’s a sample of their work:

- Improving a sense of community among residents of a local senior center

- Documenting the risk of poverty on individuals’ health

- Building a more sustainable community through community gardens, litter pickups and presentations

- Creating support networks and building leadership skills among underrepresented youths

- Tutoring of juvenile offenders at the Kansas Juvenile Correctional Complex

- Teaching U.S. citizenship to refugees

- Promoting discussion about inequality in Kansas City, Kan.

- Raising awareness about the lack of food that many KU students face

- Increasing physical activity among guests at the Lawrence Community Shelter

John Augusto, who directed the Center for Service Learning until early this year, said in an earlier interview that the annual poster event provided recognition for both students and community partners.

“We want to make sure that students understand that it’s OK to feel good about the work, but that what’s as important is that the community organization is getting a direct benefit from that work,” Augusto said. “It’s not just that I go in and I feel good about what I do but then the community organization has to clean up after my work. There really has to be a mutually beneficial relationship.”

He added: “I think what it teaches the students is that when they leave KU and they are in an environment in their professional life that’s different from what they’re used to, they need to learn to listen. A lot of times students tell us that when they’re doing this service work, and reflecting on it, they learn how to listen.”

- Tina Lai, graduate student

- Razan Mansour, undergraduate individual student award

- Jasmine Brown and Cierra Smallwood, undergraduate student group award

Short tenures vs. long-term thinking

As KU begins a search for a new provost, here’s something to keep in mind: Most provosts don’t stay in their jobs long.

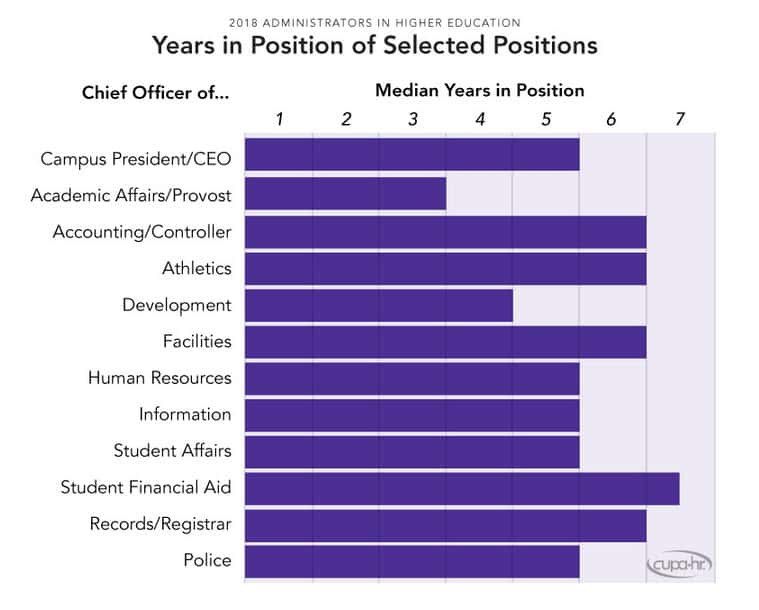

The College and University Professional Association for Human Resources says the median tenure for provosts across the country is only three years. That’s the lowest among all types of administrators the organization surveyed.

Presidents and chief executives of universities stay in their jobs at a median rate of five years, about the same as leaders of human resources and student affairs.

Jackie Bichsel, director of research for the association, is quoted as saying: “It’s not surprising that administrators overall have a relatively short median tenure. Given that those with many years of tenure do not make considerably greater salaries, their best chance of a raise may be to find a new position.”

Unfortunately, that’s the case in most jobs, both inside and outside academia. Employees sometimes talk about the “loyalty penalty,” meaning that those of us who stay at an institution for many years never get the bump in pay and other benefits that those who jump from job to job get. That becomes especially frustrating when considering that faculty salaries at KU rank near the bottom of the university’s peers.

I don’t begrudge anyone opportunities for higher pay or greater challenges. Bringing in new leaders can infuse a university with new energy and new ideas. And top leaders also feel squeezed from many sides as they take on everything from shaky budgets, rising college costs and flagging trust in higher education to polarized students and faculty, concerns about campus safety, small incidents blowing up on social media and in some cases, the survival of a university. There’s no doubt that university leaders have difficult jobs.

When those leaders change so frequently, though, a campus can easily shift to a short-term mentality. Administrators know they probably won’t stay on the job long, so they push for quick results that don’t necessarily serve the institution in the long term. Universities need to change, as I’ve written about frequently, but real change takes time, and the pressure to produce quick results makes it difficult to focus on much-needed systemic change. Quick turnover also makes it difficult to know whether leaders’ initiatives are really in a university’s best interests or whether they are simply meant to pad resumes for the next job search.

Further clouding the picture, many administrators push small initiatives but take a “wait and see” approach on innovation, preferring to let others experiment with new ideas, approaches, and technology rather than budgeting for experimentation. (Experimentation takes time, after all.) That’s one place where KU shines, at least in terms of teaching. The provost’s office has provided thousands of dollars in course transformation grants over the past few years, putting the university on the cutting edge in classroom innovations that help improve student learning. (Many of those innovations will be on display on Friday at CTE’s annual Celebration of Teaching.)

Choosing new leaders is a difficult task, as anyone who has served on a search committee can attest to. One thing seems clear, though: A university can’t rely on a single leader, or even a few leaders, to chart a path into the future. It must build a strong cohort of leaders around the university to keep the institution moving forward even as top leaders rotate in and out quickly.

Reclassifying STEM

Here’s a silly question: What is STEM?

If you said science, technology, engineering, and math, you’d be right, of course. You’d then have to explain what you mean by science, technology, engineering, and math, though.

Need help? Let’s consult the federal government.

The Department of Homeland Security says that STEM includes math, engineering, the biological sciences, the physical sciences and “fields involving research, innovation, or development of new technologies using engineering, mathematics, computer science, or natural sciences (including physical, biological, and agricultural sciences).”

That’s such a broad definition that it could theoretically apply to about anything. And that’s exactly what some universities hope to capitalize on as they try to attract more international students to the United States.

The Chronicle of Higher Education reports that universities have put such programs as economics, information science, journalism, classical art, archaeology, and applied psychology under the STEM umbrella. (Whether that will pass muster with the government remains to be seen.)

Why? Because international students who graduate in STEM fields are allowed to remain in the United States longer than those who receive non-STEM degrees, The Chronicle says. STEM graduates can work for three years in the U.S. after graduation, compared with one year for non-STEM grads.

International students, who generally pay full out-of-state tuition, have drawn increasing interest from public universities, which have struggled to make up for declining state funding. The number of international students has declined over the past couple of years, though. Nationally, there were 7 percent fewer international students in 2017-18 than in 2016-17, Inside Higher Ed reports. The largest declines were at universities in the Plains states (down 16 percent) and a region that encompasses Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana (down 20 percent). At KU, the number of international students has declined 5.5 percent since a peak in 2016, according to university data.

I’ve heard of no moves to expand the STEM classification at KU, but some other universities have given themselves wide license to reclassify programs. In other words, STEM isn’t just about science, technology, engineering, and math. It’s also about marketing.

Worth repeating

“Good teaching is emotional work, requiring reserves of patience and ingenuity that are all-too-often depleted in overworked faculty members.”

—David Gooblar of the University of Iowa, writing about faculty burnout for The Chronicle of Higher Education

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments