By Doug Ward

SAN DIEGO, Calif. – Here’s a harsh question to ask about the classrooms on our campuses: What are they good for?

Yes, there’s more than a tinge of sarcasm in that question – answering “not much” comes immediately to mind – but it gets to the heart of a problem in learning and, more broadly, in the success of our students.

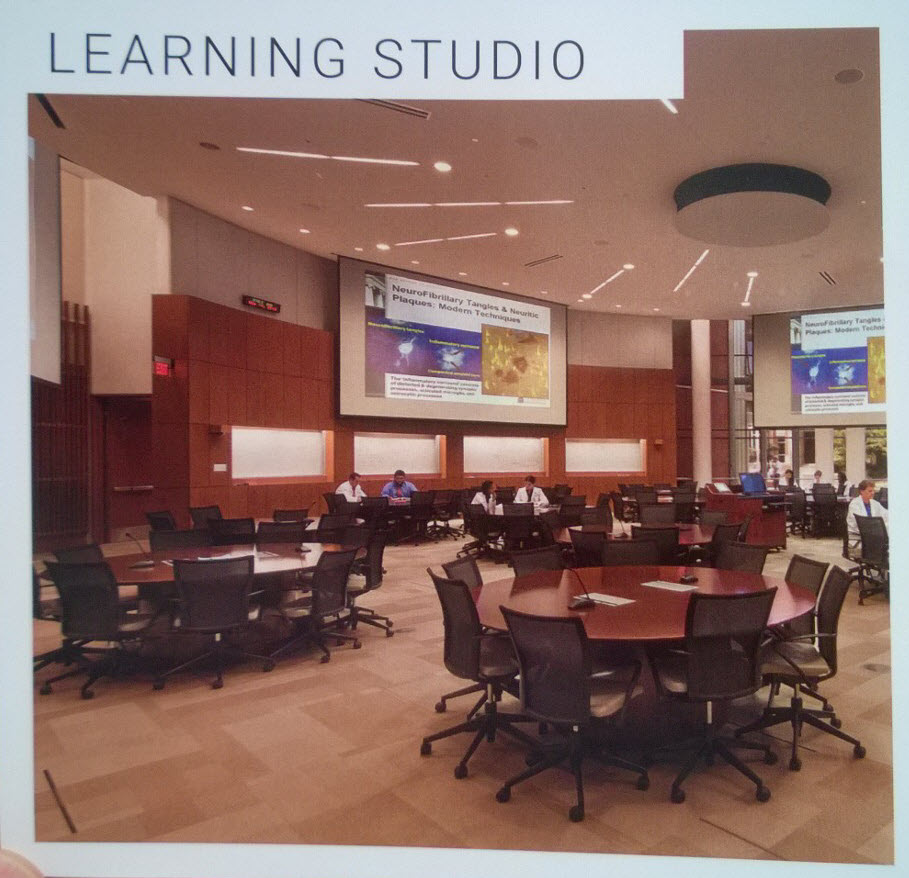

Tim Reynolds of the architecture firm TreanorHL and PK Imbrie from the University of Cincinnati asked a variation on that question this week at the Next Generation Learning Spaces conference in San Diego. At table after table in a workshop, participants said that college classrooms were designed for sitting, listening and taking notes. That is, for skills that will do our students little good in a world that requires problem solving, teamwork, strong communication skills, technical know-how, analytical ability, leadership, initiative and a strong work ethic.

“Many buildings I walk into have been rendered obsolete by new teaching styles and learning styles,” Reynolds said. “We can’t afford to be obsolete.”

Buildings alone don’t make an education, and the growth of online courses has led to many questions about the future of a traditional on-campus education. University buildings are expensive to create. They sit mostly empty for four months a year. They rarely receive the routine maintenance they need to ensure the best use, and in many cases they go neglected until they simply fall into irrelevance.

New buildings also won’t change the outdated pedagogy of recalcitrant faculty members. Nor will they solve higher education’s biggest challenge: a promotion and tenure system that rewards research almost exclusively, leaving teaching as a pesky aside.

And yet buildings are crucial to the success of students in residential education. If we plan to continue on that path in the coming decades – and most universities certainly do – then we must continue to create and re-create effective learning spaces.

And yet buildings are crucial to the success of students in residential education. If we plan to continue on that path in the coming decades – and most universities certainly do – then we must continue to create and re-create effective learning spaces.

Over and over at this week’s conference, participants grappled with the idea of creating spaces that will meet the needs of students and faculty today but that will accommodate the inevitable changes that education will face in the coming decades. That is, how do we better design buildings and classrooms to keep them relevant longer?

There’s no easy answer to that question. My answer – and that of most of the conference participants – is to focus on flexibility. For instance, creating a lecture hall with tiered concrete will make it nearly impossible to use that room for any other purpose in the future. It will simply be too expensive to change, something that universities face in many, many buildings on their campuses today. Creating flatter rooms will allow for easier reconfiguration as needs and technology change. That approach is part of a broader shift in thinking that universities must make.

“This is not changing a classroom; this is changing a culture,” Reynolds said. “It is changing what we think about as education.”

Other themes from the conference:

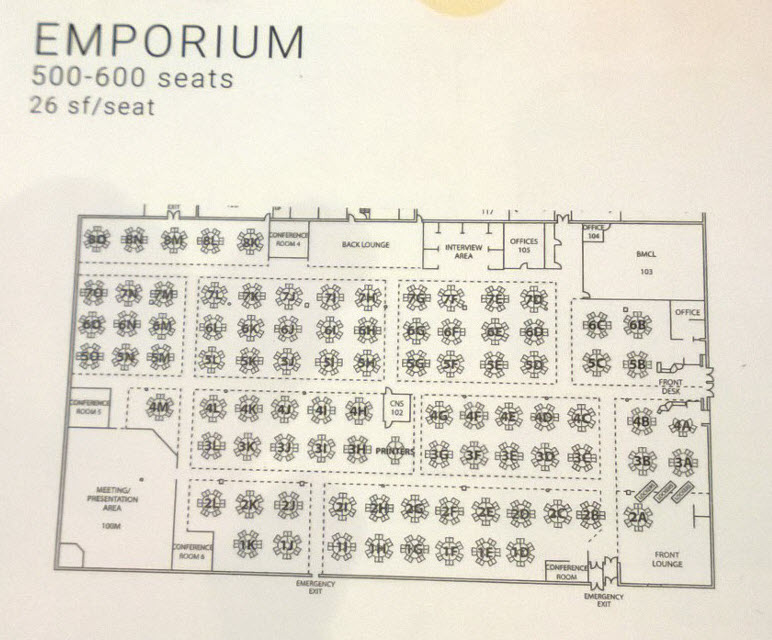

- Look beyond universities for ideas. In planning a new classroom building, Oregon State considered many non-traditional models for large classrooms, including parliament-style seating, club seating used at concerts, and in-the-round seating used in the Phil Donahue show, the iconic daytime talk show from the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. That in-the-round seating has proved especially popular among faculty, representatives from the university said, largely because even in a 600-person room, students are never more than eight rows away from the professor.

- Different spaces can inspire new approaches to teaching and learning. A new building at Oregon State contains 13 different styles of classrooms, and Jon Dorbolo, associate director of Technology Across the Curriculum, said instructors were more willing to take more chances in the way they engage students in those classrooms. (Several others at the conference made similar observations.) The variety of room styles had also helped students become more adaptable, Dorbolo said, as they learn how to learn in different settings.

- Maker spaces are hot. Universities around the country have been opening maker spaces where students have access to tools for creating with everything from robotics to sewing machines to 3D printers to engravers to digital media. Kyle Bowen of Penn State describes his university’s philosophy as “making as fluency.” Penn State has also been creating rooms where faculty and students can save whiteboards and other materials – “learning residue,” he called it – so they don’t have to start from scratch in the next class.

- Immersive experiences are growing. Virtual and augmented reality drew a lot of attention at the conference, not only with live demonstrations but with discussions about how to set up rooms to allow students to immerse themselves in alternate realities that essentially leave them blind in their physical space. Colleges are using virtual and augmented reality for such things as offering campus tours, training students in anatomy and medicine, helping students understand chemical structures, and helping them understand ancient cultures.

- Create more general purpose classroom buildings. For instance, if you label a room a genetics lab, it will go unused much of the time, Reynolds said. If you call it a classroom, many other disciplines will use it, as well. That approach also leads to a better focus on teaching and learning (rather than faculty office space) in creation of new buildings, Reynolds said.

One of my favorite descriptions from the conference came from Bowen, who spoke of two types of faculty members: FIVEs and FAVEs. FIVE, he said, stands for faculty into virtually everything. FAVE, on the other hand, refers to faculty against virtually everything. Most faculty members fall somewhere in between, but technologists and classroom schedulers must be able to accommodate the extremes, a process Bowen called the “Tetrus management” of matching classrooms to faculty needs.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments