By Doug Ward

The criticism of liberal education often carries a vicious sting. For instance, listen to Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor:

“Universities ought to have skin in the game. When a student shows up, they ought to say, ‘Hey, that psych major deal, that philosophy major thing, that’s great. It’s important to have liberal arts … but realize, you’re going to be working at Chick-fil-A.’”

Or Gov. Matthew Bevin of Kentucky as he describes his budget priorities for higher education:

“There will be more incentives to electrical engineers than to French literature majors. All the people in the world that want to study French literature can do so. They are just not going to be subsidized by the taxpayer like engineers.”

Those sorts of disparaging comments certainly demonstrate an ignorance of higher education, but they also reflect the use of higher education as a political foil as the cost of college – and student debt – rises. Those simplistic characterizations have power. They stick in people’s minds and play into stereotypes of academia as an ivory tower separate from society at large and out of touch with the vast majority of Americans. They also reflect a growing emphasis on college as a job factory rather than a place to help citizens learn to think more deeply and more critically, and to expand their understanding of a complex and ever-changing world.

Higher education has done a poor job of pushing back against those criticisms, as I wrote earlier this week. Faculty members and administrators are eager to do better, though, as I found last week in a workshop I led at the annual meeting of the Association of American College and Universities in Washington. I gave participants a handout in which I had categorized common criticisms of liberal education and provided examples like the ones above. After a brief discussion, I asked them to identify an audience and create their own messages to address one or more of the criticisms. The results were excellent, showing a steely resolve to reclaim the reputation of higher education.

Categorizing criticisms

I generally see six types of criticisms of liberal education. Most come from outside the academy, but some come from inside. There are overlapping aspects among all of them, and no doubt there are others. (For instance, one workshop participant pointed out the complaint that the liberal arts focuses heavily on the ideas of long-dead white men.) These are the common ones that I’ve identified, though, and that I shared in the workshop:

- College costs too much to waste on “impractical” subjects

- The study of the liberal arts has become an anachronism

- Liberal education is out of touch with the “real world”

- Liberal education isn’t keeping up with a changing world

- Liberal education has lost its meaning

- Identity consciousness has tainted liberal education

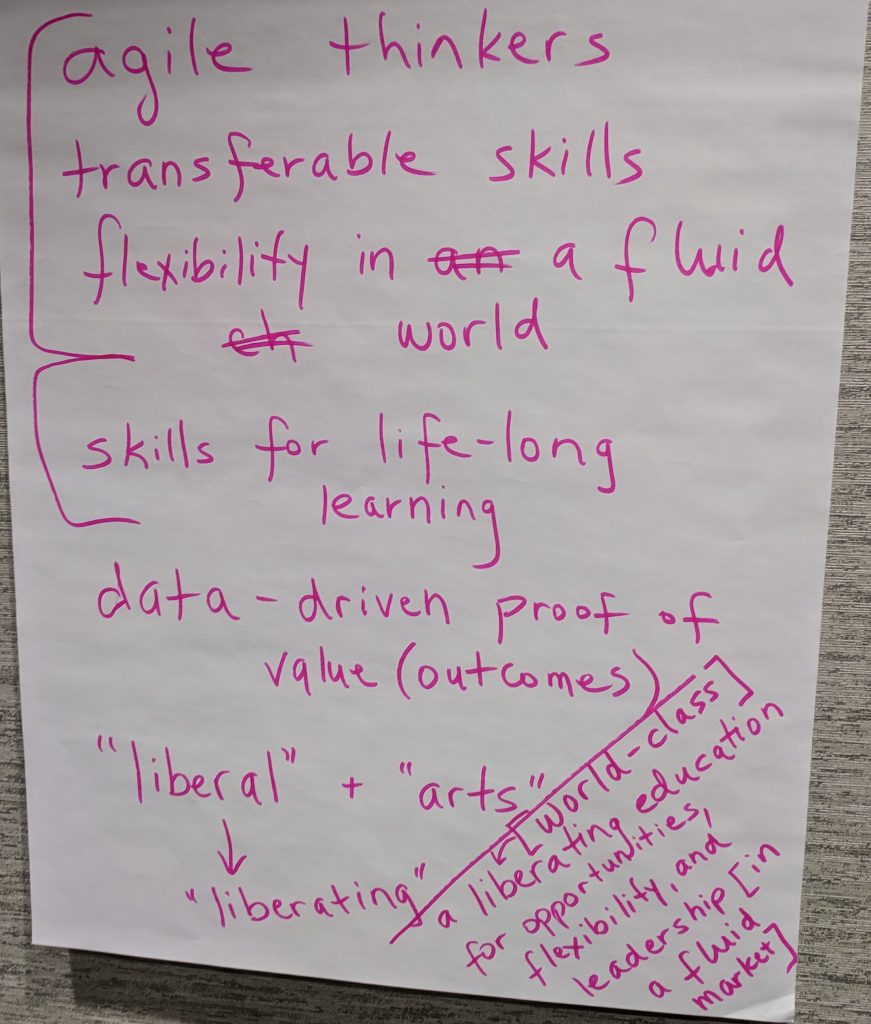

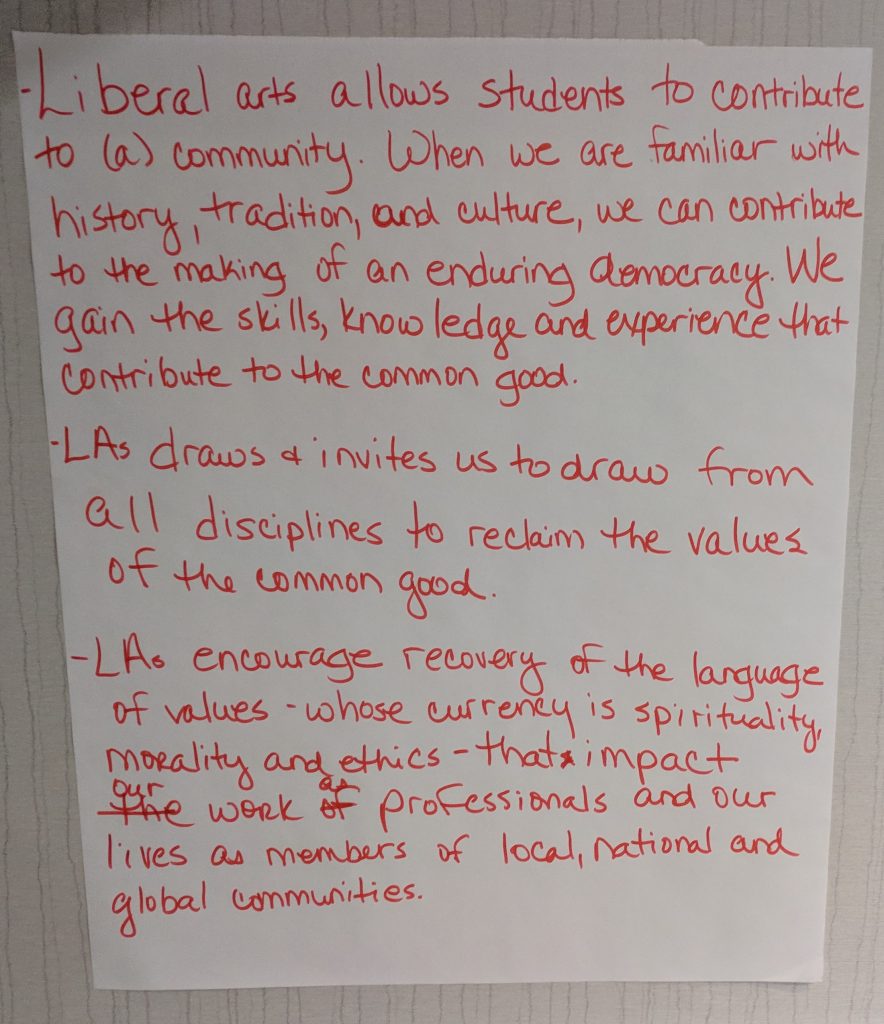

I asked workshop participants to work in pairs or groups, choose one or more of those criticisms, and create both a soundbite and more substantial messages that highlight the strengths of liberal education. Some rejected the idea of soundbites. That’s understandable. Matching soundbite to soundbite can easily devolve into the equivalent of a playground brawl rather than a meaningful conversation. Nonetheless, I think it is important that we distill the importance of liberal education into key elements to use when talking with students, parents, donors, community members, politicians, and even colleagues.

Here are examples of how workshop participants rose to that challenge:

- Change is a constant. Liberal education provides the means to create and navigate that change.

- Liberal education is a pedagogy and an ethos, not a set of disciplines.

- Finding a path and a voice in the world.

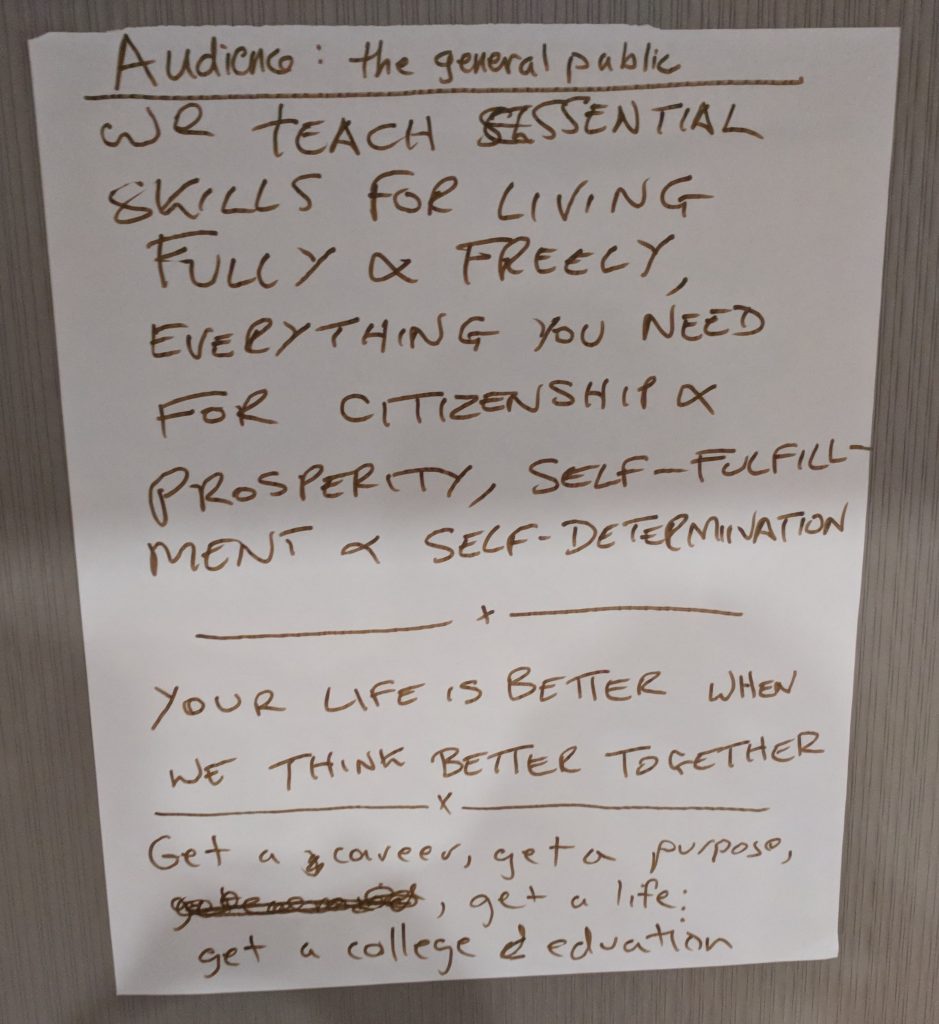

- Your life is better when we think better together.

- Get a career, get a purpose, get a life, get a college education.

- Build a team that knows how to think.

- Liberal arts will get your promotion.

- Pivot for your next opportunity.

- Invest in the long run.

- We teach essential skills for living fully and freely, everything you need for citizenship and prosperity, self-fulfillment and self-determination.

Two groups focused specifically on Republican donors, drawing on the language of business to make a connection:

- Liberal education builds workplace skills: adaptability, flexibility, communication skills, evaluation and analytical skills, interpersonal skills in diverse populations. It also instills ethics and fosters curiosity.

- The liberal arts yields effective communication skills in multiple modes, which is core to successful messaging, interaction, negotiation, innovation, collaboration, creative problem-solving, sales and marketing, global perspective, diverse audiences and cultures.

As I said, there are dangers in trying to compress the complexities of liberal education into soundbites or even more substantial talking points. We will never do it justice. By thinking in those terms, though, we can better identify the components of higher education we want to emphasize and better prepare ourselves for conversations with a broad range of constituencies.

So let’s keep talking.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments