By Doug Ward

The ASU GSV Summit bills itself as a gathering of entrepreneurs, policymakers, business leaders and educators who want “to create partnerships, explore solutions, and shape the future of learning.”

That sort of described the event, which was held last week in San Diego. Yes, it was possible to find a few real discussions about education, but only a few. Doug Lederman of Inside HigherEd estimated that 10 percent of the 3,500 attendees came from colleges and universities, though many of those came from Arizona State, which is the “ASU” in the summit name. (GSV is a Silicon Valley investment firm.)

Many of the sessions that addressed higher education took a critical, if not condescending, tone toward colleges and universities. Many speakers criticized educators for being slow to adopt technology (I agree) and failing to prepare students for high-paying jobs in technology (as if that is the only path). One session on the future of higher education had no educators. (If you figure that one out, let me know.)

A robot roamed the floor during the ASU GSV Summit

That shouldn’t have surprised me. Far too many technology vendors emphasize the magic of technology without having any real understanding of the educational process. They make their pitch to school and university technology departments, which too often buy the technology and present it gleefully to educators, only to find that the educators have no use for it.

Thankfully, many educational technology entrepreneurs do have an understanding of education, and many of their products evolve from experiences with family members or friends. And educators and IT departments are learning to speak with one another. At KU, we have created collaborations among IT, instructors and administrators. The process isn’t perfect, but we all feel that we are making much better decisions about technology through a shared vetting process.

I saw some of that sort of thinking at the conference, with entrepreneurs explaining partnerships with school districts and universities to test products, gather feedback, and revise the technology. One speaker even urged educators to demand evidence that products work as promised, something he said few schools and colleges did.

Bill Gates, in his keynote, made an excellent observation: Much of educational technology lacks any connection to the educational system. We need to figure out ways of working together to create a process of continuous improvement, he said.

I agree. Higher education needs desperately to change, as I’ve written about many times. But simply throwing technology at the problems won’t do anything but raise costs. Too often, vendors want to sell their products but don’t want to listen – really listen – to how those products are or are not used, and how feedback from educators could help improve those products. They also fail to do their homework about existing technologies that colleges and universities use, and explain how their products work with or improve upon existing platforms.

I love to explore new digital tools, but when it comes to technology for my students or for the university, I approach purchases with these questions in mind:

- How will this help student engagement and student learning?

- How steep is the learning curve?

- Is it truly better than something we already have?

- Will it integrate into the technology we have?

- Is the cost justified?

- Could we do this cheaper and better ourselves?

Until educators and tech entrepreneurs can talk frankly about those sorts of questions, we will be stuck in a cycle of finger-pointing and distrust.

Themes from the summit

Several themes emerged from the sessions I sat in on and the products I saw at the summit. Goldie Blumenstyk of The Chronicle of Higher Education pointed out two: mentorship tools and programs that help students connect to jobs. I agree, but as I wrote earlier this week in highlighting some promising digital tools, I’m looking at this through my lens as a professor.

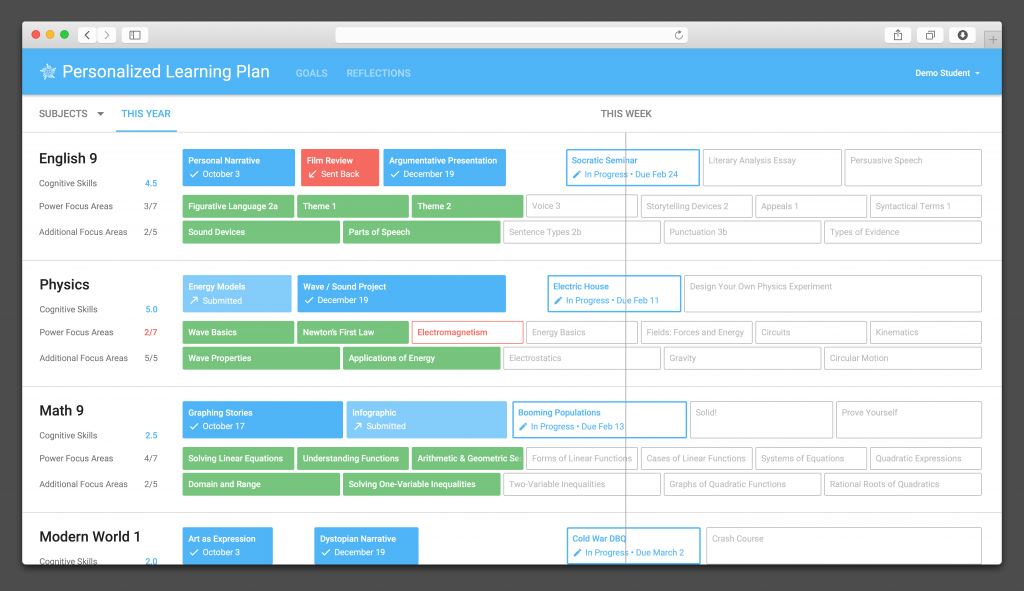

Personalized and adaptive learning. These are in some ways the holy grail of education and certainly of educational technology. Entrepreneurs and educators have tried for a century to create technology that adapts to students’ learning needs, as Bill Ferster writes in his book Teaching Machines. Digital technology has reinvigorated that push, even as truly reliable adaptive, individualized learning remains elusive.

Data, data, data. We’ve been hearing about data in education (and everything else) for years, and tech vendors have taken note. Nearly every new product contains some element of data gathering and display.

Virtual reality. An exhibit room called Tomorrowland contained several tools for engaging students with virtual environments. Some used technology-enabled headsets; others used smartphones inside cardboard goggles. Again, this is no surprise, though it seems more of a stepping stone than a long-term direction for education.

Tools to help students write. This reflects a general decline in reading and writing skills that many of us in higher education have seen. Whether these tools, which provide structure and advice, can truly improve writing remains to be seen. I see potential in some, though I don’t want students to become overly reliant on technology for writing and thinking.

Tools to help students learn coding. Again, no surprise here, especially amid a widespread call for students to tap into the potential of digital technology and move into technology-related jobs.

Tools for developing online course material. Understandable given the spread of online and hybrid courses.

Social connection and peer evaluation. These run the gamut from platforms for reaching out to students through text messaging to apps for peer tutoring and goal tracking.

None of these themes is revolutionary, and many have been evolving for years. They do represent a cross-section of where entrepreneurs see opportunity in education.

A final thought

Tim Renick of Georgia State said higher education did a poor job of gathering evidence about what works and what doesn’t work in our own institutions. We have almost no research on academic advising, he said. Nor do faculty members base their own curriculums on evidence. Rather, he said, “we go to faculty meetings and make stuff up.” In a note of hope, though, he added: “We are becoming more data literate, and as that data falls into the hands of faculty, it is leading to change.”

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments