By Doug Ward

KU’s big jump in freshman enrollment this academic year ran counter to broader trends in higher education.

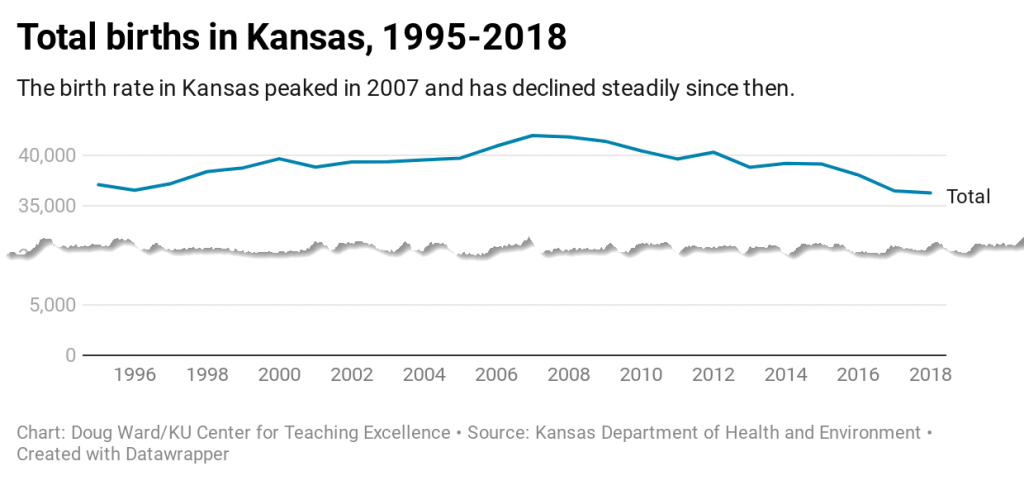

Around the country, college enrollment has been trending downward (although there was a slight increase in 2023), many campuses have been closing or consolidating, and a lower birthrate after the 2008-09 recession looms in what has become known as the “enrollment cliff.” That is, with fewer births, there will soon be fewer students graduating from high school and thus fewer potential college applicants.

Even so, KU was one of only 10 flagship universities where overall enrollment declined in the 2010s, according to a Chronicle of Higher Education analysis. In the fall, though, freshman enrollment increased 18%, to 5,259, the largest freshman class ever. If current trends continue, there may be another growth spurt next year. But why?

Flagships as backups

The university has credited the increase to reputation, recruitment strategies, increases in financial aid, and an improved football team. I have no doubt that recruitment strategies and financial aid played a significant role, and reputation always matters. I look for broader (often cultural) trends, though. Jeff Selingo, who writes about admissions, innovation, and the future of higher education, offers some possible explanations in his latest email newsletter. Selingo argues that many students, especially those in the top 5% to 10% of incomes, are going to state flagship universities if they don't get into top-ranked schools. He writes:

What I’m finding in my book research is that some families are increasingly skipping over this next ring of institutions from the very top because they don’t get good offers of merit aid. So, instead, the families chase dollars from a set of institutions deeper in the rankings or the kid heads off to an honors college at a flagship public with a low net price (sometimes zero) and lots of perks, like early access to course registration and sponsored research projects with faculty.

This idea of let’s try for Ivy U., and then if not, State U. has been common in some places like Georgia and Florida for decades ...

He highlights another trend that is certainly affecting KU: out-of-state enrollment growing faster than in-state enrollment.

“Nearly every public flagship enrolled a smaller share of freshmen from within their states in 2022 than they did two decades earlier,” Selingo said, citing a Chronicle analysis of data from the Department of Education.

At KU, the percentage of freshmen from Kansas fell to perhaps its lowest ever (56%) in Fall 2023, according to data from Analytics, Institutional Research, and Effectiveness. That is a decline of 13.1 percentage points from 2002, when in-state students made up 69.1% of the freshman class, according to the Chronicle analysis.

The number of Kansas students enrolled as freshmen at KU actually rose to at least a 10-year high, but the number of out-of-state students rose even more, with the university attracting more students from such states as Missouri, Nebraska, Illinois, Iowa, Colorado, Minnesota, and Oklahoma.

The declining percentage of in-state freshmen at KU is actually less substantial than that at some other state universities. Here are a few examples from nearby states, drawing on data from the Chronicle analysis.

% of in-state freshmen at state flagship universities

| University | 2002 | 2022 | Change (in %pts.) |

| Colorado | 54.9 | 53.6 | -1.3 |

| Iowa | 59.5 | 53.8 | -5.7 |

| Nebraska | 82.9 | 73 | -9.9 |

| KU | 69.1 | 57.6 | -11.5 |

| Missouri | 82.6 | 69.9 | -12.7 |

| South Dakota | 67 | 52.8 | -14.2 |

| Illinois | 89.2 | 71.4 | -17.8 |

| Indiana | 65.1 | 52.3 | -17.8 |

| Ohio State | 84.6 | 66.7 | -17.9 |

| Wisconsin | 64.2 | 43.8 | -20.4 |

| Oklahoma | 76.3 | 52.9 | -23.4 |

| Arkansas | 80.5 | 39.3 | -41.2 |

If the trends that Selingo indentified hold, KU could see continued growth among out-of-state students, especially those with family incomes of $160,000 and up. The trends also suggest that attracting those students will require higher levels of financial aid, admission to the honors program, and opportunities to work with individual faculty members. In other words, out-of-state students who are rejected by the Ivy League and similar highly ranked schools expect more perks from KU and other state flagship universities.

The sudden growth has brought in additional money to the university, but Jeff DeWitt, KU's chief financial officer, said in a presentation in November that the university had spent millions of additional dollars on scholarships, instructors, advisors, and housing.

"Record enrollment is not free," DeWitt said.

The trends that are benefiting KU and other state flagship universities have made recruitment more difficult at regional universities, the Chronicle reports. Among Kansas regents universities, for instance, only KU (4.1%) and Wichita State (5.1%) have increased enrollment over the past decade. Three others have had dramatic decreases: Pittsburg State (-25.7%), Emporia State (-25.1%), and K-State (-21.5%). Fort Hays State’s enrollment fell 5.7% during the same period. (I’ve excluded the medical center and K-State’s veterinary medicine program, both of which have increased in enrollment but are still relatively small.)

All of that portends a very different look to higher education in Kansas in the coming years.

Are student-athletes employees?

A case before the National Labor Relations Board could force colleges and universities to designate athletes as employees and to pay them as such, Politico reports.

Depending on your perspective, that could either give student-athletes what they are rightfully owed or lead to the collapse of college sports, Politico says.

One passage from the Politico article offered an interesting interpretation on how colleges and universities have looked at athletes:

Pro-labor advocates argue that schools’ “student-athlete” designation is a legal term of art originally designed to shield institutions from player workers’ compensation claims. It deprives competitors of fair compensation for their talents or influence over the system that governs much of their day-to-day college experience, they note.

The NCAA and colleges and universities say, however, that college sports would not survive in their current form if designations were changed. As a result, Politico said, they may seek intervention from Congress if the NLRB forces them to pay athletes.

A ruling is expected in the early spring.

Doug Ward is an associate director at the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Recent Comments