By Doug Ward

A young woman with a flower headdress caught my attention as I walked through Budig Hall earlier this week. I stopped and asked her what the occasion was.

“It’s Hat Day in Accounting 200,” she said.

I wanted to know more, and Paul Mason, who teaches the 8 a.m. section of the class, and Rachel Green, who teaches the 9:30 section, graciously invited me in.

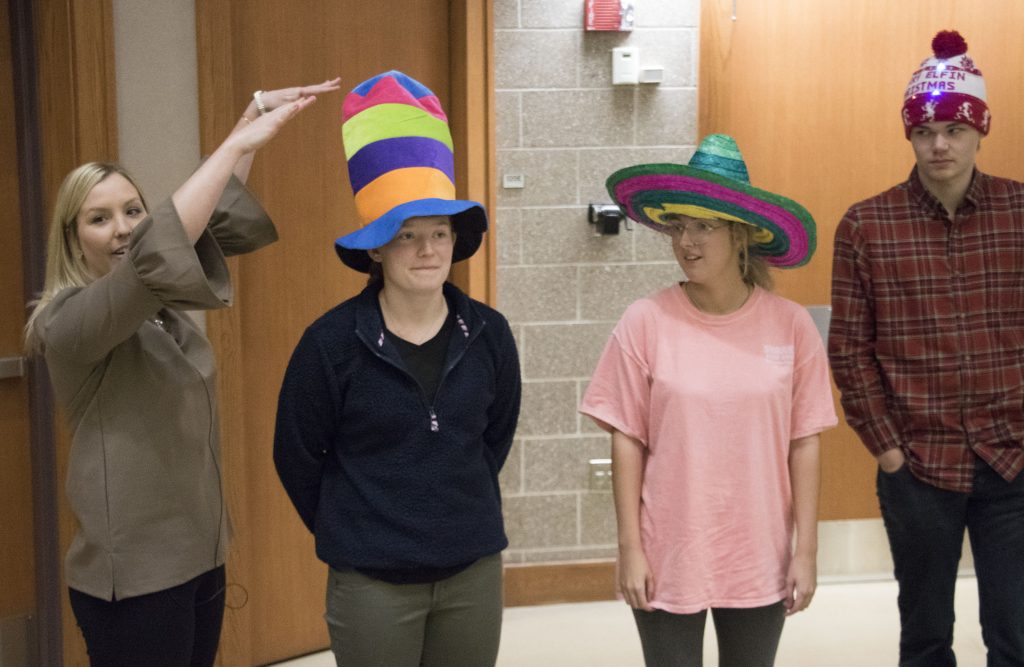

Hat Day, they said, is a tradition that goes back 20 years. It takes place one day toward the beginning of each semester and works like this: Students get a bonus point if they wear a hat to class. Teaching assistants choose what they consider the best hats from their sections of the class. Those students (who get another extra point) come to the front of the room, and a winner is chosen based on student applause. The winner gets one more extra point, for a total of three.

Hat Day serves two purposes, Mason said. Accounting 200 is the introductory course for the business school, and Hat Day helps instructors make the point that accountants wear many hats on the job and that students can do many things with an accounting degree.

Just as important, he said, it allows students to see the lighter side of business.

“It’s our way of letting them know that accounting isn’t just numbers,” Mason said.

It serves one more purpose: creating a sense of camaraderie among the students. Each section of the class has upward of 500 students, and the clapping and cheering on Hat Day loosens things up a bit.

“When they’re in a big class and they start laughing, it makes the class smaller,” Mason said.

A new way to provide online instruction

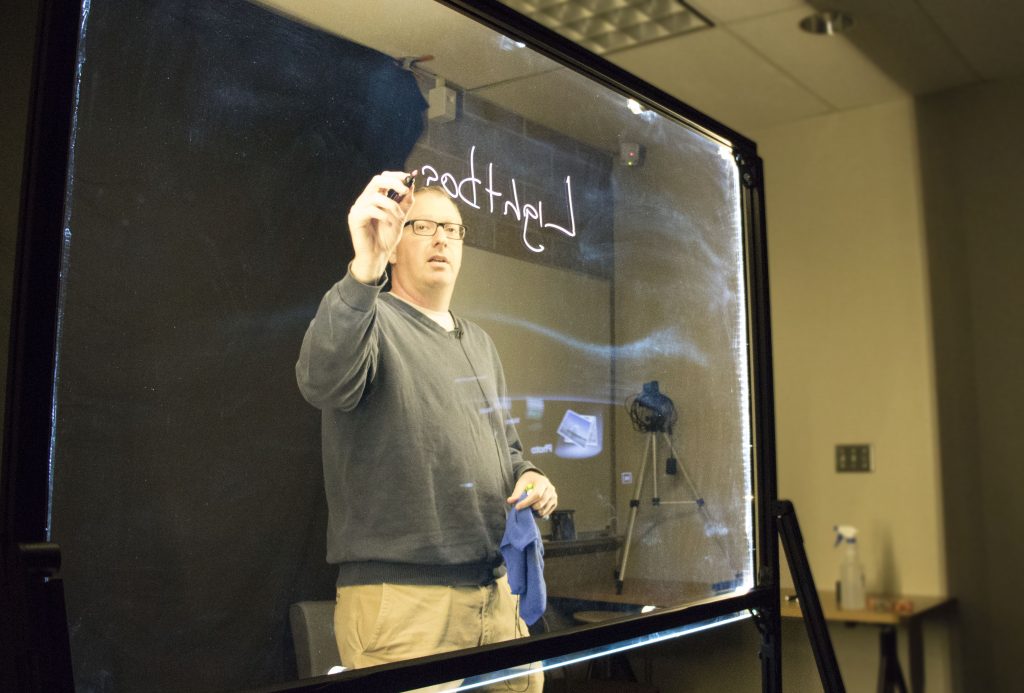

A new device created by staff members from Information Technology and the Center for Online and Distance Learning will allow faculty members to record instructional videos through an illuminated pane of glass they write on like a whiteboard.

Development of the device, known as a lightboard, was led by John Rinnert of IT. A faculty member created the first video on the lightboard last week, and after a demonstration of the board this week, Rinnert expects more people to sign up to use it.

The board is a large pane made from the same type of glass as shower doors, Rinnert said. The glass rests in a metal frame, and LED track lighting gives markings on the board a neon glow as users write and draw. Another track of LEDs faces out, illuminating speakers as they write.

Instructors will soon have the ability to superimpose graphics on an area of the glass, much like a television weathercast. Instructors who do that will have to watch a monitor as they write so they can see where the graphics are placed.

Rinnert, Julie Loats from CODL, Anne Madden Johnson from IT, and I started talking about obtaining a lightboard a few years ago as a way to draw more faculty members from math and sciences into creating flipped and hybrid courses. Any faculty member is welcome to use the board, but those in STEM fields who do a a lot of on-board problem-solving should find it a familiar environment in which to work.

I wrote about a similar device that students in Engineering Physics 601 created last year. That lightboard is still awaiting a permanent home in Malott Hall.

At a session we did this week, Loats pointed out how important it is for students to hear instructors explain their thought processes as they work through problems. Many instructors do that effectively in the classroom and in videos they create without being on camera. The lightboard offers another tool for them in preparing material for online and hybrid courses.

Those interested in using the board can contact either CODL or IT.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments