By Doug Ward

After a session at the KU Teaching Summit last week, I spoke with a faculty member whose question I wasn’t able to get to during a discussion.

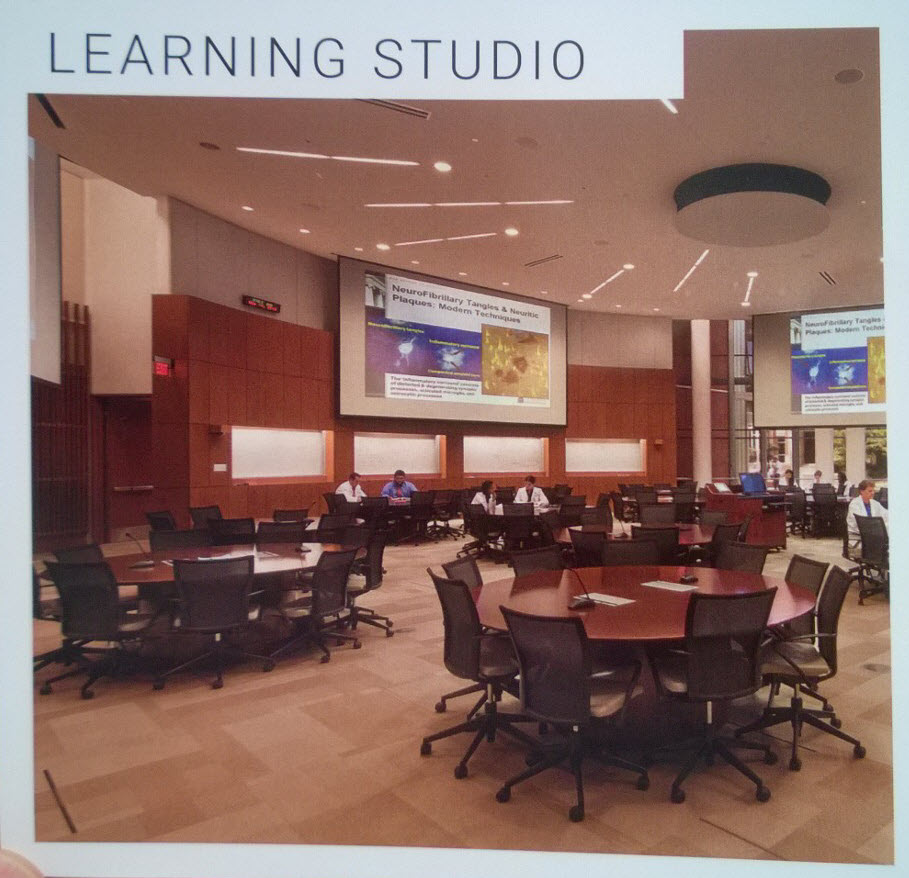

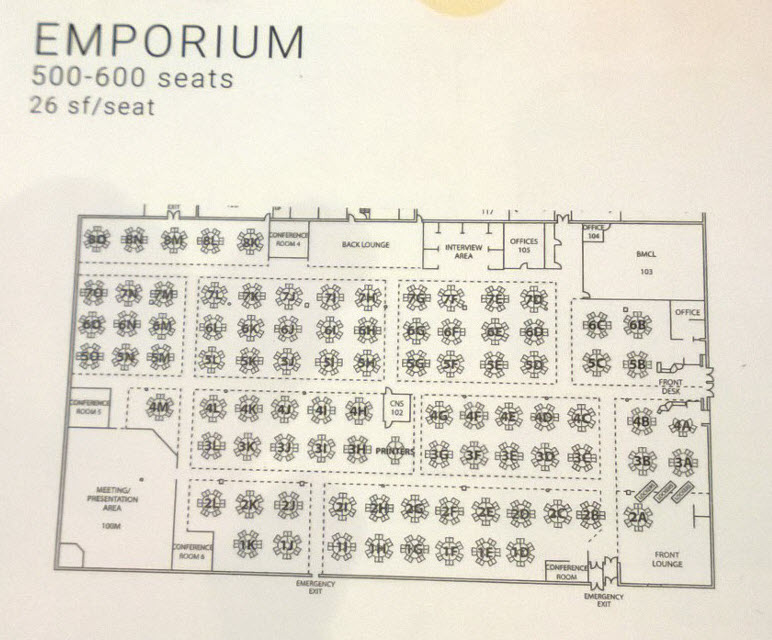

The session, Classrooms and the Future of Education, focused on how KU is working to create and renovate classrooms for active learning. Universities around the country are doing the same, putting in movable tables and chairs, and adding nontraditional furniture, whiteboards, monitors, and various digital accoutrements to make collaboration and hands-on learning easier, and learning environments more inviting.

The faculty member at my session said rooms alone would accomplish nothing unless instructors changed their approach to teaching. I agreed with him wholeheartedly. Effective pedagogy must come first, and many faculty members have created active learning environments in classrooms build solely for lecture. The redesigned classrooms are simply a means of providing flexibility in the environment and of allowing students to work together more easily.

Larry Cuban, a professor emeritus at Stanford, made much the same point about technology earlier this month.

Technology, Cuban said, is simply a tool, and its power to effect change is only as great as the person using it. Its ability to enhance thinking, engagement, learning or a host of other things depends largely on how it is used.

He drove that point home by explaining how technology companies have starting using “engagement” as a code word for student achievement. In pushing schools to buy new digital tools, companies rarely promise that technology alone will lead to improved learning. Rather, they say that digital devices and software will improve student engagement, as if engagement alone were a magic elixir.

It’s not.

Engagement matters, Cuban says, but it works alongside elements like classroom structure, student-instructor relationships, varied teaching techniques, and student grit. To those I’d add instructor and student preparedness; informed pedagogy; students’ willingness to learn about and engage with challenging ideas; and meaningful assignments, among other things.

“Anyone who says publicly that student engagement triggered by new hardware and software will produce higher achievement is selling snake oil,” Cuban writes, citing a litany of studies rejecting the idea that more technology leads to improved learning.

We need to help students learn to use technology to search for and analyze information; to solve problems, and to convey ideas. We need to provide more flexibility in the physical spaces of our classrooms to inspire collaboration and creativity.

None of those things matter, though, if instructors ignore the needs of their students, fail to engage them with challenging questions and course material, focus on information delivery rather than learning, and disregard the pedagogical lessons we have learned about a new generation of students.

Learning requires hard work from instructors and their students. Classrooms matter. Technology matters. But neither provides a magical solution.

Another take on classrooms

Edutopia recently published three articles that offer additional perspectives on remaking classrooms. All focus on K-12 education, but they offer valuable perspectives on the types of classrooms our future students will be used to using.

At Albemarle Public Schools in Virginia, students can sit at a table, on a couch or on the floor. They can stand if they prefer or even lie down. Teachers often furnish their classrooms with inexpensive furniture they buy from Goodwill or from college students moving out of town. Parents donate furniture, and some teachers have even used crowdfunding to raise money for furniture. (I’ve never seen those approaches used in higher ed, but I like the idea.)

Heather Wolpert-Gowran, a middle school teacher in California, writes about her switch to a new classroom, saying she moved everything except the tables and chairs. She plans to experiment with various types of seating, and she writes about her journey toward finding the right mix.

Finally, Todd Finley, a regular contributor to Edutopia, writes about concepts and research on classroom design. He also provides links to many examples of redesigned classrooms at elementary schools, middle schools and high schools.

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments