By Doug Ward

If you plan to use student surveys of teaching for feedback on your classes this semester, consider this: Only about 50% of students fill out the surveys online.

Yes, 50%.

There are several ways that instructors can increase that response rate, though. None are particularly difficult, but they do require you to think about the surveys in slightly different ways. I’ll get to those in a moment.

The low response rate for online student surveys of teaching is not just a problem at KU. Nearly every university that has moved student surveys online has faced the same challenge.

That shouldn’t be surprising. When surveys are conducted on paper, instructors (or proxies) distribute them in class and students have 10 or 15 minutes to fill them out. With the online surveys, students usually fill them out on their own time – or simply ignore them.

——————————————————————————————————————

——————————————————————————————————————

I have no interest in returning to paper surveys, which are cumbersome, wasteful and time-consuming. For example, Ally Smith, an administrative assistant in environmental studies, geology, geography, and atmospheric sciences, estimates that staff time needed to prepare data and distribute results for those four disciplines has declined by 47.5 hours a semester since the surveys were moved online. Staff members now spend about 4 hours gathering and distributing the online data.

That’s an enormous time savings. The online surveys also save reams of paper and allow departments to eliminate the cost of scanning the surveys. That cost is about 8 cents a page. The online system also protects student and faculty privacy. Paper surveys are generally handled by several people, and students in large classes sometimes leave completed surveys in or near the classroom. (I once found a completed survey sitting on a trash can outside a lecture hall.)

So there are solid reasons to move to online surveys. The question is how to improve student responsiveness.

I recently led a university committee that looked into that. Others on the committee were Chris Elles, Heidi Hallman, Ravi Shanmugam, Holly Storkel and Ketty Wong. We found no magic solution, but we did find that many instructors were able to get 80% to 100% of their students to participate in the surveys. Here are four common approaches they use:

Have students complete surveys in class

Completing the surveys outside class was necessary in the first three years of online surveys at KU because students had to use a laptop or desktop computer. A system the university adopted two years ago allows them to use smartphones, tablets or computers. A vast majority of students have smartphones, so it would be easy for them to take the surveys in class. Instructors would need to give notice to students about bringing a device on survey day and find ways to make sure everyone has a device. Those who were absent or were not able to complete the surveys could still do so outside class.

Remind students about the surveys several times

Notices about the online surveys are sent by the Center for Online and Distance Learning, an entity that most students don’t know and never interact with otherwise. Instructors who have had consistently high response rates send out multiple messages to students and speak about the surveys in class. They explain that student feedback is important for improving courses and that a higher response rate provides a broader understanding of students’ experiences in a class.

To some extent, response rates indicate the degree to which students feel a part of a class, and rates are generally higher in smaller classes. Even in classes where students feel engaged, though, a single reminder from an instructor isn’t enough. Rather, instructors should explain why the feedback from the surveys is important and how it is used to improve future classes. An appeal that explains the importance and offers specific examples of how the instructor has used the feedback is more likely to get students to act than one that just reminds them to fill out the surveys. Sending several reminders is even better.

Give extra credit for completing surveys

Instructors in large classes have found this an especially effective means of increasing student participation. Giving students as little as 1 point extra credit (amounting to a fraction of 1% of an overall grade) is enough to spur students to action, although offering a bump of 1% or more is even more effective. In some cases, instructors have gamified the process. The higher the response rate, the more extra credit everyone in the class receives. I’m generally not a fan of extra credit, but instructors who have used this method have been able to get more than 90% of their students to complete the online surveys of teaching.

Add midterm surveys

A midterm survey helps instructors identify problems or frustrations in a class and make changes during the semester. signaling to students that their opinions and experiences matter. This in turn helps motivate students to complete end-of-semester surveys. Many instructors already administer midterm surveys either electronically (via Blackboard or other online tools) or with paper, asking students such things as what is going well in the class, what needs to change, and where they are struggling. This approach is backed up by research from a training-evaluation organization called ALPS Insights, which has found that students are more likely to complete later course surveys if instructors acknowledge and act on earlier feedback they have given. It’s too late to adopt that approach this semester, but it is worth trying in future semesters.

Remember the limitations

Student surveys of teaching can provide valuable feedback that helps instructors make adjustments in future semesters. Instructors we spoke to, though, overwhelmingly said that student comments were the most valuable component of the surveys. Those comments point to specific areas where students have concerns or where a course is working well.

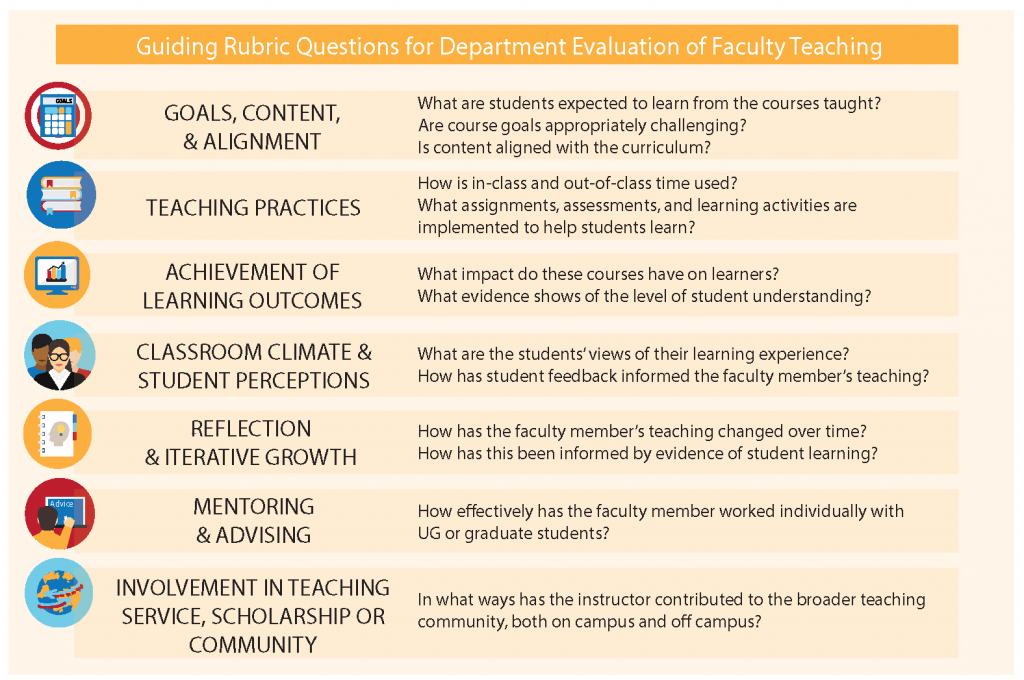

Unfortunately, surveys of teaching have been grossly misused as an objective measure of an instructor’s effectiveness. A growing body of research has found that the surveys do not evaluate the quality of instruction in a class and do not correlate with student learning. They are best used as one component of a much larger array of evidence. The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences has developed a broader framework, and CTE has created an approach we call Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness. It uses a rubric to help shape a more thorough, fairer and nuanced evaluation process.

Universities across the country are rethinking their approach to evaluating teaching, and the work of CTE and the College are at the forefront of that. Even those broader approaches require input from students, though. So as you move into your final classes, remind students of the importance of their participation in the process.

(What have you found effective? If you have found other ways of increasing student participation in end-of-semester teaching surveys, let us know so we can share your ideas with colleagues.)

The ‘right’ way to take notes isn’t clear cut

A new study on note-taking muddies what many instructors saw as a clear advantage of pen and paper.

The study replicates a 2014 study that has been used as evidence for banning laptop computers in class and having students take notes by hand. The new study found little difference except for what it called a “small (insignificant)” advantage in recall of factual information for those taking handwritten notes.

Daniel Oppenheimer, a Carnegie Mellon professor who is a co-author of the new paper, told The Chronicle of Higher Education:

“The right way to look at these findings, both the original findings and these new findings, is not that longhand is better than laptops for note-taking, but rather that longhand note-taking is different from laptop note-taking.”

A former KU dean worries about perceptions of elitism

Kim Wilcox, a former KU dean of liberal arts and sciences, argues in Edsource that the recent college admissions scandal leaves the inaccurate impression that only elite colleges matter and that the admissions process can’t be trusted.

“Those elite universities do not represent the broad reality in America,” writes Wilcox, who is the chancellor of the University of California, Riverside. He was KU’s dean of liberal arts and sciences from 2002 to 2005.

He speaks from experience. UC Riverside has been a national leader in increasing graduation rates, especially among low-income students and those from underrepresented minority groups. Wilcox himself was a first-generation college student.

He says that the scandal came about in part by “reliance on a set of outdated measures of collegiate quality; measures that focus on institutional wealth and student rejection rates as indicators of educational excellence.”

Wilcox was chair of speech-language-hearing at KU for 10 years and was president and CEO of the Kansas Board of Regents from 1999 to 2002.

Join our Celebration of Teaching

CTE’s annual Celebration of Teaching will take place Friday at 3 p.m. at the Beren Petroleum Center in Slawson Hall. More than 50 posters will be on display from instructors who have transformed their courses through the Curriculum Innovation Program, C21, Diversity Scholars, and Best Practices Institute. It’s a great chance to pick up teaching tips from colleagues and to learn more about the great work being done across campus.

Doug Ward is the acting director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments