By Doug Ward

AUSTIN, Texas – How do students view effective teaching?

They offer a partial answer each semester when they fill out end-of-course teaching surveys. Thoughtful comments from students can help instructors adapt assignments and approaches to instruction in their classes. Unfortunately, those surveys emphasize a ratings scale rather than written feedback, squeezing out the nuance.

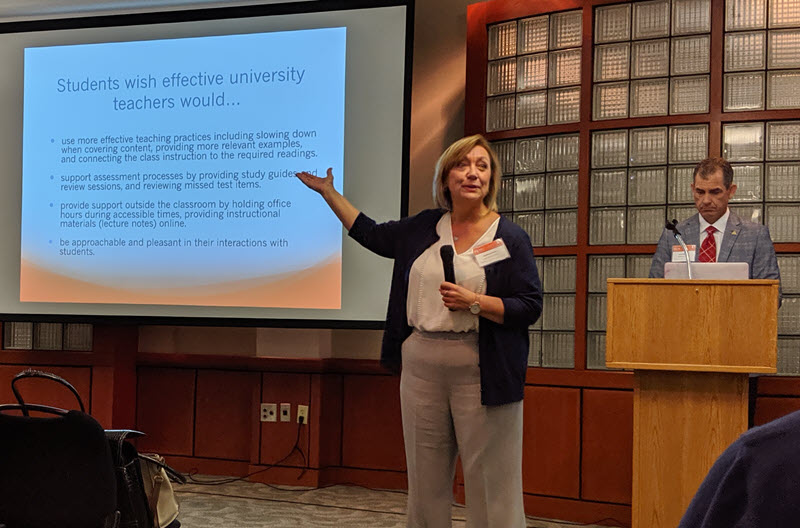

To address that, staff members from the Institute for Teaching and Learning Excellence at Oklahoma State spoke with nearly 700 students about the effectiveness of their instructors and their classes. They compiled that qualitative data into suggestions for making teaching more effective. Christina Ormsbee, director of the center at OSU, and Shane Robinson, associate director, shared findings from those surveys last week at the Big 12 Teaching and Learning Conference in Austin.

Here are some of the things students said:

- Engage us. The students’ favorite instructors vary their approach to class, use interesting and engaging instructional methods, and use relevant examples.

- Communicate clearly. Students value clear assignments, transparent communication, and timely, useful feedback. They also want lecture notes posted online.

- Be approachable. Students described their favorite instructors as personable, professional and caring. “Students really want faculty to care about them,” Ormsbee said. They also want instructors to care about student learning. They complained about instructors who were abrasive, sarcastic or demeaning.

- Align class time with assessments. Students want instructors to respect their time by using class activities and lessons that connect to out-of-class readings and build toward assessments.

- Be available. Students want instructors to hold office hours at times that are convenient for students and to help them when they ask. They also expect instructors to communicate through the campus learning management system and though email and other types of media.

- Be organized. Students appreciate organizational tools like detailed class agendas and timelines. They like study sessions before exams, but they also want instructors to go over material they missed on exams.

- Slow down. Students say instructors often go through course material too quickly.

- Grade fairly. Students dislike instructors who focus grading too heavily on one aspect of a course, grade too harshly, or deduct points for missing class or for not participating.

- Don’t give us too much work. (You aren’t surprised, are you?)

Much of this aligns with the research on effective teaching and learning (engagement, alignment, organization, pacing, transparency, clarity). Some of it also aligns with aspects of universal design for learning (see below). Other aspects have as much to do with common courtesy as with good pedagogy. (We all want to feel respected.) Still other parts reflect a consumer mentality that has seeped into many aspects of higher education.

Feedback from students is important, but it is also just one of many things that instructors need to focus on. A class of satisfied students means nothing if none of them is learning. And students know little about the years of accumulated evidence about effective teaching. So we should listen, yes, but we should base decisions about our classes on an array of evidence and thoughtful reflection.

Universal design takes center stage

All too often, instructors, administrators and staff members think about accessibility of course content only when a student requests an accommodation.

The problem with that approach, said Melissa Wong of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is that a vast majority of students who need accommodations never seek them out. Sometimes they don’t know about a disability or have never been formally diagnosed. In other cases, students are embarrassed about having to share personal details or assume they can make it through a class without an accommodation.

Wong called the current system of acquiring an accommodation “legalistic.” Students must have health insurance. They must fill out multiple forms and have records transferred. They must maneuver through university bureaucracy and find the right offices, a skill that many students lack. Then they must submit forms in each class they take. In class, they may confront inaccessible course materials, hazy expectations, and daunting assignments.

Each of those barriers adds to students’ burden, ultimately making things harder for instructors and for other students. Instructors can help all their students – even those who don’t need accommodations – by following the principles of universal design for learning, though, Wong said. Wong was among several speakers at the Big 12 conference who emphasized the importance of universal design for learning.

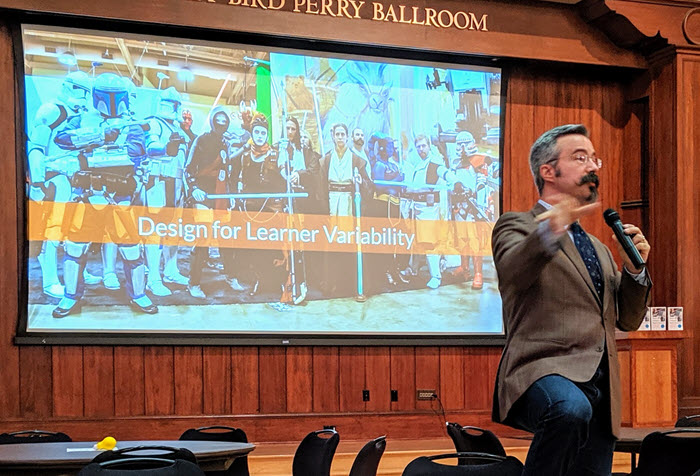

Universal design started with architecture (think curb cuts and self-opening doors), but its importance in education has grown as the diversity of students has grown. In essence, it is a way of thinking about learning in terms of student choices: multiple forms of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple forms of action and expression.

Tom Tobin of the University of Wisconsin-Madison suggested thinking of universal design in terms of “plus one.” If you have a written assignment, consider giving students one other option for completing the same work. If you provide a video, make sure it has captions.

“We don’t have to perfect,” Tobin said. “We just have to be good.”

He also suggested reframing the conversation about accessibility to one about access. Good access helps all students learn more effectively and keeps them moving toward graduation.

“The idea of UDL is not to lower the rigor of the material,” Tobin said. “The idea is to lower the barrier of getting into the conversation in the first place.”

Wong offered some additional advice on how to apply universal design in classes:

- Use a clear organizational structure in your syllabus. Use subheads so that students can find everything easily. And make sure the syllabus has a section on accommodations.

- Create a list of assignments and due dates. This helps students plan and cuts down on anxiety. Wong said a one-page assignment calendar she creates was one of the most popular things she had done for her classes.

- Present information in a variety of ways (text, video, audio, multimedia), and provide examples of successful work. Offering choices in assignments can help students feel more in control and allow them to demonstrate learning in ways they are most comfortable with. For instance, you might give students a range of assignment topics to choose from and give them options like video or audio for presenting their work, in addition to writing.

- Make sure video is close-captioned. If you have audio, make sure students have access to a transcript.

- Use a microphone routinely, especially in large classrooms.

- Scaffold assignments so that students can work toward a goal in smaller pieces.

- Be flexible with deadlines. If you give one student an extension, make sure all students have the same option. If a student is chronically late with assignments or frequently seeks to make up work, try to understand the underlying problems and refer that student to offices on campus that can help.

The best approach is to take accessibility into account from the beginning rather than trying to retrofit things later, Wong said. That not only cuts down on the need for accommodations but creates a smoother route for all students.

Other nuggets from the conference:

Supplemental instruction success. A three-year study at the University of Texas-Austin found that student participation in supplemental instruction sessions improved grades in gateway courses in electrical engineering. Supplemental instruction involves regular student-led study sessions overseen by trained student facilitators. About 40% of students in UT’s Introduction to Electrical Engineering courses participated in supplemental instruction. I’ll be writing more about KU’s supplemental instruction program in the next few weeks.

Practical thinking. Shelley Howell of the University of Texas-San Antonio emphasized the importance of relevance in helping students move toward deeper learning. She drew on a model from Ken Bain’s book What the Best College Students Do, categorizing students into surface learners (who do just enough to get by), strategic learners (who focus on details and stress about grades) and deep learners (who are curious and ask questions, accept failure as a part of the learning process, and apply learning across disciplines). All students need to understand the purpose of individual assignments, and instructors need to make course content relevant, give students choices, and ask questions that take students on a “messy” path to understanding, Howell said.

Red alert. Educators have grown too complacent about student failure, Howell said, and would benefit from a Star Trek approach to student success. Every episode of Star Trek is essentially the same, she said: Something goes wrong. The problem must be fixed right away or the ship will crash. The problem is impossible to fix. The crew finds a way to fix it anyway. What if those of us in higher education had the same attitude? Howell asked, adding: If you knew that every student had to succeed, how would you teach differently?

A final thought. Emily Drabinski, a critical pedagogy librarian at the Graduate Center at City University of New York, offered this bit of wisdom: “For knowledge to be made, it has to be organized.”

Doug Ward is the associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism. You can follow him on Twitter @kuediting.

Recent Comments