By Doug Ward

The intellectual work that goes into teaching often goes unnoticed.

All too often, departments rely on simple lists of classes and scores from student surveys of teaching to “evaluate” instructors. I put “evaluate” in quotation marks because those list-heavy reviews look only at surface-level numerical information and ignore the real work that goes into making teaching effective, engaging, and meaningful.

An annual evaluation is a great time for instructors to document the substantial intellectual work of teaching and for evaluators to put that work front and center of the review process. That approach takes a slightly different form than many instructors are used to, and at a CTE workshop last week we helped draw out some of the things that might be documented in an annual review packet and for other, more substantial reviews.

Participants shared a wide range of activities that showed just how creative and devoted many KU instructors are. The list might spur ideas for others putting together materials for annual review:

Engagement and learning

Nearly all the instructors at the workshop reported modifying classes based on their observations, reviews of research, and student feedback from previous semesters. These included:

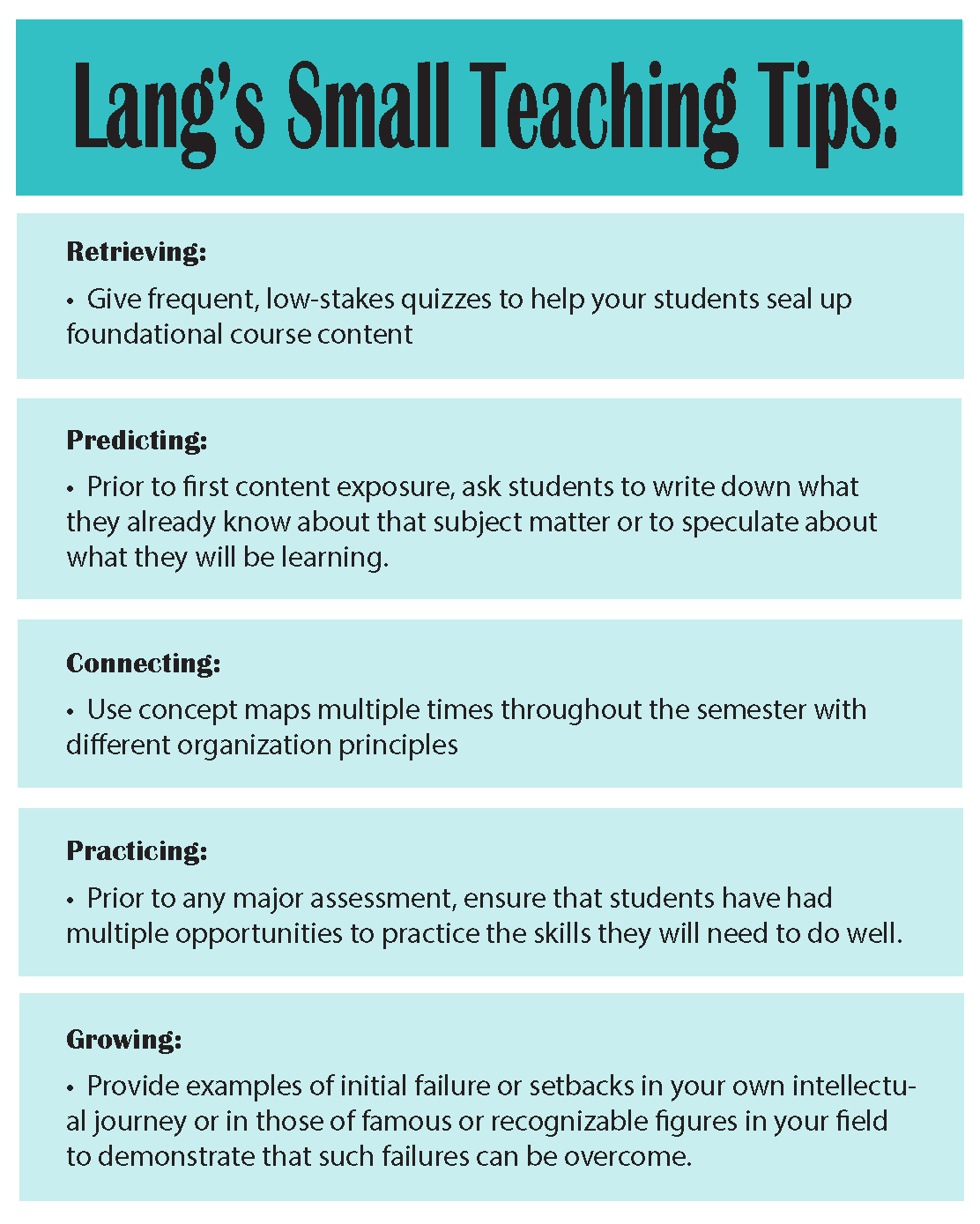

- Moving away from quizzes and exams, and relying more on low-stakes assignments, including blog posts, minute papers, and other types of writing assignments to gauge student understanding.

- Moving material online and using class time to focus on interaction, discussion, group work, peer review, and other activities that are difficult for students to do on their own.

- Using reflection journals to help students gain a better understanding of their own learning and better develop their metacognitive skills.

- Providing new ways for students to participate in class. This included adding a digital tool that allows students to make comments on slides and add to conversations the way they do through online chats.

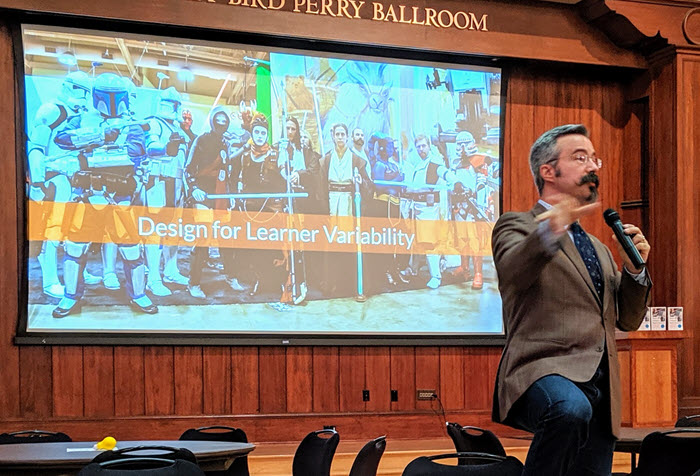

- Using universal design to provide choices to students for how they learn material and demonstrate their understanding.

- Scaffolding assignments. Many instructors took a critical look at how students approached assignments, identifying skills in more detail, and helping students build skills layer by layer through scaffolded work.

- Bringing professionals into class to broaden student perspectives on the discipline and to reinforce the importance of course content.

- Creating online courses. In some cases, this involved creating courses from scratch. In others, it meant adapting an in-person course to an online environment.

- Rethinking course content. Sarah Browne in math remade course videos with a lightboard. That allowed students to see her as she worked problems, adding an extra bit of humanity to the process. She also used Kaltura to embed quizzes in the videos. Those quizzes helped students gauge their understanding of material, but they also increased the time students spent with the videos and cut down on stopping part-way through.

Overcoming challenges

- Larger class sizes. A few instructors talked about adapting courses to accommodate larger enrollment or larger class sizes. More instructors are being asked to do that each semester as departments reduce class sections and try to generate more credit hours with existing classes.

- Student engagement. Faculty in nearly all departments have struggled with student engagement during the pandemic. Some students who had been mostly online have struggled to re-engage with courses and classmates in person. As a result, instructors have taken a variety of steps to interact more with students and to help them engage with their peers in class.

- Emphasis on community. Instructors brought more collaborative work and discussion into their courses to help create community among students and to push them to go deeper into course material. This included efforts to create a safe and inclusive learning environment to bolster student confidence and help students succeed.

- Frequent check-ins. Instructors reported increased use of check-ins and other forms of feedback to gauge students’ mood and motivation. This included gathering feedback at midterm and at other points in a class so they could adjust everything from class format to class discussions and use of class time. At least one instructor created an exit survey to gather feedback. David Mai of film and media studies used an emoji check-in each day last year. Students clicked on an emoji to indicate how they were feeling that day, and Mai adapted class activities depending on the mood.

Adapting and creating courses

The university has shifted all courses to Canvas over the last two years. Doing so required instructors to put in a substantial amount of time-consuming work. This included:

- Time involved in moving, reorganizing, and adapting materials to the new learning management system.

- Training needed through Information Technology, the Center for Online and Distance Learning, and the Center for Teaching Excellence to learn how to use Canvas effectively and to integrate it into courses in ways that help students.

Ji-Yeon Lee from East Asian languages and culture went even further, creating and sharing materials that made it easier for colleagues to adapt their classes to Canvas and to use Canvas to make courses more engaging.

Resources on documenting teaching

CTE has several resources available to help instructors document their teaching. These include:

- A page on representing and reviewing teaching has additional ideas on how to document teaching and student learning, and how to present that material for review. One section of the page includes resources on how to use results from the new student survey of teaching.

- A page for the Benchmarks for Teaching Effectiveness project has numerous resources related to a framework developed for evaluating teaching. These include a rubric with criteria for the seven dimensions of effective teaching that Benchmarks is based on; an evidence matrix that points to potential sources for documenting aspects of teaching; and a guide on representing evidence of student learning.

Documenting teaching can sometimes seem daunting, but it becomes easier the more you work on it and learn what materials to set aside during a semester.

Just keep in mind: Little of the intellectual work that goes into your teaching will be visible unless you make it visible. That makes some instructors uncomfortable, but it’s important to remember that you are your own best advocate. Documenting your work allows you to do that with evidence, not just low-level statistics.

Doug Ward is an associate director at the Center for Teaching Excellence and an associate professor of journalism and mass communications.

Recent Comments