By Derek Graf

Critics of liberal education seem obsessed with immediate practicality. Or at least the visibility of practicality.

For example, Gallup advises higher education institutions to “demonstrate their value to consumers by increasing their alignment with the workforce.” The author also suggests that the field of liberal arts might attract more students after some “rebranding” to avoid the political connotations associated with the word “liberal.” Such a name change, the logic goes, would allow the humanities to promote and emphasize their relevance to students of the 21st century. A post on Gallup’s website responds to a poll in which many U.S. adults expressed concerns about the financial stability, value, and overall effectiveness of higher education.

Note the language used to describe the basic structure of the university: With students as consumers, colleges must compete for their business. In an earlier post, I discussed the problems that arise from conflating teaching with customer service. From that perspective, graduation seems less an accomplishment than a financial transaction, and the human element of learning becomes marginalized for the sake of careerism.

How can the humanities demonstrate their value—often intangible—to students? As Elizabeth H. Bradley explains in a recent Inside Higher Ed article, students who study the liberal arts have a strong capacity to “recognize the larger patterns of human behavior.” While I agree with her observation, it’s still difficult at first glance to say exactly how the study of literature, visual art, photography, film, and so on prepares students for the non-academic workforce. But that’s what makes the humanities more vital than ever.

Perhaps I’m an idealist, but I don’t believe that we should measure the success of a liberal arts education by the statistics of job placement. Without such statistics, how does one measure the growth and development of students as human beings in the higher education system? As Gianpiero Petriglieri claims in a recent post for Harvard Business Review, “once they stop having to be useful, the humanities become truly meaningful.”

The idea here is that a central tenet of the humanities—concern for and exploration of the human condition—becomes lost when this particular field of study functions only as an instrument for financial or occupational satisfaction. The capitalist pursuit does a disservice to humanistic education, because it ignores the potential for literature and art to make an impact in the context of social justice, for example, or to raise awareness about historical and systemic inequalities. Outside the narrow perspective of the workforce, the humanities have tremendous value. Studying the humanities isn’t practical or pragmatic in any materialist sense, and it shouldn’t have to be.

Must everything be marketable?

But to return to an earlier question raised by the Gallup post: what is the workforce? Is this the same arena as the “real world” that is so often held up as an intimidating contrast to one’s college years? If so, then the workforce offers a range of opportunities for which higher education institutions cannot completely account.

While universities can provide internships and training courses for specific occupations, the idea of a workforce is too nebulous for any cohesive design at alignment. Structural attempts to holistically align the university curriculum with the job market will change the university into a vocational school. If that happens, then students will not have access to courses—in the humanities, for example—that offer no practical advice or preparation for a particular job.

So what happens if, instead of promoting “marketable skills” and “essential qualities” for a student’s future career, humanities courses emphasize their lack of practicality, their resistance to pragmatism? In an article for the Intercollegiate Review, James Matthew Wilson says that “the primary task of liberal education is to plant your mind with images of the good and the beautiful, images to which you are naturally drawn, often without knowing why.”

The good and the beautiful, sure, but also the bad and the ugly, to which many of us are also naturally drawn. Rather than present literature, art, and film as timeless texts that hold timeless truths, as Wilson does, it’s important to communicate to students that one seeks out the humanities for problems, not for answers. For ways not to act, as well as for models of ethical and moral behavior.

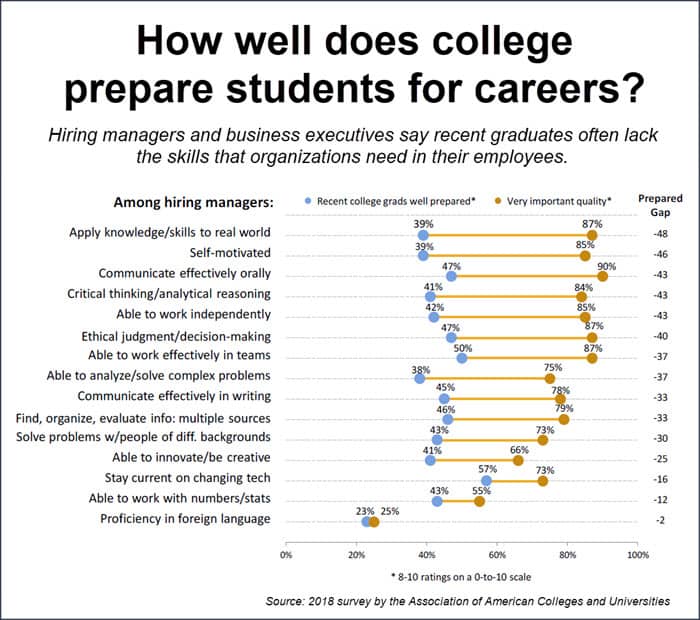

Studying the humanities in a rigorous, committed manner helps students acquire skills that will benefit them as applicants and employees. As Gerald Greenberg explains in this Washington Post article, humanities students bring to the workplace valuable “problem-solving and critical thinking abilities.” These skills are not specific to any particular job. Instead, they apply to a range of occupations. An education in the humanities might seem opaque to those who seek a one-to-one correlation between one’s degree and one’s career. However, with greater consideration of the actual tasks and exercises presented to students in humanities courses, it becomes more and more clear how well-equipped such students are for work both inside and outside the academy.

Of course, college is expensive, and many students likely believe that visual arts or creative writing courses offer nothing but a waste of time and money. It’s beyond the means of this post to offer a solution for the rising costs of higher education, but I don’t think that the answer for the humanities lies in emphasizing productivity and practicality. Instead, a liberal arts education should present itself in honest, direct terms: these classes are frustrating, challenging, and often overwhelming in their scope. And yet, while students won’t necessarily be able to apply the content of such courses to their future occupations, they will be able to deal with the many frustrations, challenges, and overwhelming sensations that arise in any workplace environment. The humanities offer a distinct, unorthodox path to job preparation, one that finds comfort in the uncomfortable.

The thinking process is crucial

In my experience as an instructor of creative writing (poetry, short fiction, literary nonfiction, etc.) and composition, I have seen my students struggle with the practice of writing or reading just for the sake of writing or reading. “Are we going to turn this in?” or “Is this for a grade?” are common questions I encounter when I ask students to perform a free-writing exercise or dialogue activity, for example. There are a few problems that arise in this scenario. One of them is that when I tell my students that they will not turn in or be graded for such writing, many students simply don’t do the work. They don’t see the practical value of composition when it isn’t tied to a grade. The central question behind this response is, to my mind, “What’s the point?”

I understand and sympathize with their frustration, but I also want them to embrace that feeling, to work in a space of indeterminacy, and see what they can produce under those circumstances. My attempt is to discourage even more troubling questions that often arise in writing classes: “What do you want me to say?” or “If I say this will I get an A?” I refuse to treat my students like employees, to give them narrow confines of expression, to reduce all writing in the academic space to a letter grade.

Why? Because unlike Wilson, I do not believe that “critical thinking” encourages a “skeptical, suspicious view of the world.” Instead, it’s my opinion that critical thinking, which students must perform independently to achieve the higher-end goals of a particular assignment, allows for a more comprehensive and considerate view of the world.

The value of the humanities, then, lies in the processes of critical thinking, interpretation, discernment, and deliberation. It might not be possible to tell from a prospective employee’s transcript that her Introduction to American Literature course required these forms of mental and emotional work, but it will certainly become clear over time that such skills often originate from the tasks one performs in humanities courses. These classes have long-term rather than short-term benefits, and without them (or without encouragement to enroll in them), any alignment for the workforce will have serious gaps in its foundation.

Derek Graf is a graduate fellow at the Center for Teaching excellence and a graduate teaching assistant in English.

Recent Comments